Pandemic. Great resignation. Remote work. Supply chain chaos. This environment wasn’t what Andrew Lingel expected to encounter when he succeeded his father as CEO of United Plastic Fabricating (UPF), a medium-sized manufacturing firm headquartered in Massachusetts, in 2017.

Despite these challenges, UPF doubled its productivity between 2017 and 2021 without adding resources. And its goal is to nearly double it again by the end of 2022. Each time they break a “ship-dollar-per-hour” (their productivity metric) record, they frame and hang a broken record — literally, a broken record — in their Massachusetts headquarters’ lobby. It’s starting to look like the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

UPF manufactures water tanks for firetrucks. No two municipality firetrucks are the same, as local fire chiefs determine their design. According to FEMA, there are nearly 30,000 fire departments in the United States. Because the water tank’s design is based on the void that remains following the installation of everything else, UPF’s engineers and factory workers must design, cut, and weld some gnarly shapes that are rarely identical. It’s a classic high-mix, low-volume environment.

Lingel was determined to become profitable when he took over the company and decided lean could pave that path to profitability: “I felt like that to continue to charge our customers more money for our inefficiencies wasn’t a good recipe for the long-term.”

Getting Involved in Plant-floor Improvement

Initially, the company focused on shopfloor kaizen. When the Massachusetts plant manager left, Lingel stepped in to learn as much as possible as fast as possible. Working alongside continuous improvement leader Tim Rossetti, the team transitioned from craft to flow manufacturing. Previously, operators built tanks from start to finish in fixed stations. Lingel and Rossetti divided the work content across several stations and balanced it to a three-hour takt time.

Other changes they made to help operators work efficiently included the following:

- color-coding tools and built shadow boards to prevent searching for equipment

- moving parts and tools closer to workstations to reduce walking and reaching

- redesigning work to make welding the tank’s large plastic sheets less strenuous

- leveling the production schedule by mixing high-work-content tanks with low-work-content tanks to ease operator burden and reduce bottlenecks.

Within two years, they increased productivity by 60%.

Applying Lean Thinking to Design Engineering

The factory’s gains created an unexpected problem: design engineering could not keep pace and had fallen 91 jobs behind the shop floor. As a result, the three plants were at risk of sitting idle, waiting on engineering to send new prints.

To keep pace with production, design engineering needed to release 60 drawings per week. At the time, their output was 38.

UPF’s design engineering process is more repetitive than creative; engineers do not imagine a new tank with every order. Instead, they take a customer’s specifications and build them in CAD. They repeat the same steps with each order, just like operators on the floor. For example, instead of “weld flange,” a designer’s work element looks like “Make sure gussets are scalloped in corner for easier welding.” This insight led Lingel to transform design engineering using flow just like they had transformed manufacturing.

Making this change was no small feat because engineers hardly saw their work as repetitive. Instead, they saw each tank as a unique challenge that demanded their full talents. Each day, an engineering manager dished out assignments for the day, and engineers plugged away until it was ready for manufacturing. With his flow line proposal, Lingel upended this approach. Rather than build from start to finish, engineers would complete one of several design stages and then handoff to another engineer.

Helping Engineers Understand ‘Why’

To support the transformation, Lingel brought in Rossetti from the shop floor. His job was to bring kaizen know-how to engineering. “First, I got engineers to understand that balance was key,” Rossetti said. Bottlenecks result when work content is not balanced across stations. So, if one operator has 30 minutes of work while the adjacent one has 10 minutes of work, the consequence is 20 idle minutes. Moreover, work content should be balanced to takt time — the pace of customer demand — to enable an organization to produce just what the market requires.

While engineers had successfully broken down the job of designing a tank into discrete steps, they had not balanced them equally between the stations, causing bottlenecks. Rossetti helped them get seven stations leveled to a 40-minute takt time. So 60 tanks per week translated to 12 tanks per day or one tank every 40 minutes.

Next, the team leveled the schedule. “A 3,000-gallon tank could come right after a 1,000-gallon tank, which could leave people idle,” he explained. They enacted two countermeasures. First, the line leader started to mix the schedule to balance low-work-content tanks and high-work-content tanks. Second, when a high-work-content tank entered the line, he moved a second engineer to the same station to begin work on a low-work-content tank to ensure they produced one tank every ninety minutes.

Getting Design Engineers on Board

Initially, engineers were reluctant, especially highly skilled engineers whose pride and sense of value came from their ability to design the most complex tanks. Suddenly, they were being asked to do a seemingly trivial job even new engineers could do. Moreover, a mistake could quickly lead to blaming after a handoff. Senior engineer Ken Vachon commented, “You feel like the finger is pointing at you because you did something wrong. And you take it personally.”

Twice-daily meetings changed everything. They gave the team a forum to raise and resolve problems the system uncovered. For instance, handoffs from one engineer to another revealed that UPF had no design standards. Instead, each engineer had their own. The differences were so substantial that the factories prioritized tanks from certain engineers because the prints were easier to build!

Before long, finger-pointing evolved into problem-solving. The engineers discovered the clever tricks that were previously buried in their heads and turned them into common standards. Soon the job became as much about designing tanks as learning how to design tanks more effectively. Vachon reflected, “I started to understand that it’s not about blaming people for problems. It’s a learning system to gather insights so problems do not recur.”

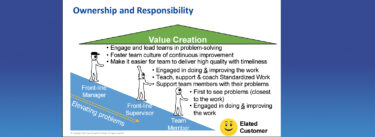

LEI coach Karl Ohaus, who has worked with UPF since 2017, talked about this transformation in thinking, “On factory floors, the size of the tool chest tells you how experienced the maintenance person is — and it’s a matter of pride for them. For UPF design engineers the size of the tool chest was capability to handle complex designs. They had to go from my tools and my capability to our tools and our capability. They had to learn to open the tool chest up and share that knowledge. And the way to share that knowledge is building standardized work. Then value creation becomes solving problems as a team to make that standardized work better.”

Another common problem was the long delays and idle engineers caused by the need for engineers to communicate frequently with the customer to clarify specifications. As a result, Vachon established a new team of three engineers between sales and engineering to debug customer drawings. If something wasn’t clear or incorrect, an engineer immediately contacted the customer to address the problem. Consequently, all drawings that reached the first stage of design engineering were 100% complete and accurate, enabling flow through the final stage.

While every customer’s order is different, tank designs are similar. Previously, design engineers started every new order from scratch. So, in addition to debugging drawings, Vachon’s team began pulling similar tanks from UPF’s archive to give engineers a head start on every order. Making this immediately shaved 30 to 60 minutes off the design time.

The transformation has also accelerated skills development. For example, with the craft-build system, it could take months or years before a new engineer could build a complex tank without supervision. In the flow system, new engineers can effectively work almost immediately because they must master only one station at a time.

Moreover, the team tracks defects not just by the station but by the person. Current print production manager Sammy Toby explained, “This allows us to see whether it’s a person having an issue or if the station is just too difficult, resulting in problems for everyone.” If the former, Toby knows where to target training; if the latter, he knows where to focus the team’s problem-solving efforts. Previously, engineers’ — especially skilled ones — solution to poor productivity was, “He should just work like I do!” Now, the design engineers see poor performance as either a fault in the system or an opportunity to skill up an engineer.

After only a few months, design engineering consistently hit 58 to 60 tanks per week — a 78% to 84% increase from their original output of 38.

After only a few months, design engineering consistently hit 58 to 60 tanks per week — a 78% to 84% increase from their original output of 38. Moreover, manufacturing’s productivity increased another 13% because the quality of the prints was so much better. “I owe it to the line process because we stopped sending defective prints to the floor,” Vachon said.

Despite working 100% remotely and across four states, the design engineering team feels like a team now more than ever. Working together off a simple Excel spreadsheet, handing over and receiving work, and meeting twice a day helped build a team spirit that did not exist even when everyone worked in the same office.

UPF has developed into a learning organization with a relentless appetite for problem-solving. Consequently, crisis or no crisis, the broken records will likely continue to pile up.

Great article really showed how Lingel had to restructure the whole model. And now instead of only pushing out 38 tanks per week they are doing 58 to 60 per week while doing all of this remotely. The really have cracked the code and by doing this just through Excel spreadsheets and meeting twice day I think is very impressive. Like you said it built the teams spirit up that wasn’t even up when they were in the office. Again great post really showed how Lingel embraced the lean way and transitioned from craft to flow manufacturing and was successful with the outcome.

This article is a great example of continuous improvement and how the implementation of lean six sigma can have a major increase on productivity. It was very interesting to learn how UPF was able to use Kaizen and continue to improve their production system very quickly. It was also interesting to learn how UPF was able to apply creative lean thinking into design engineering to help reduce bottlenecks. I was very surprised to read at the end of the article that the design engineering team worked 100% remotely and across four states. I think the team would have been even more successful if they were present on the floor and able to see everything that was happening.

really nice article. very applicable to the type of company i work at (high mix, low volume, design engineering bottlenecks).