There is no questioning the essential nature of coaching as a core skill of lean leadership. If lean is a matter of learning new skills and even mental models, learning lean is a “learn by doing” or experiential learning process. And if lean is an experiential learning process, coaching is THE skill to enable more effective, more efficient learning of lean thinking and practice. It’s a skill that all lean leaders need to acquire.

Lean Leadership, According to Art Byrne

Leading through lean thinking sometimes creates conflict. Consider even how leaders often feel forced to make a choice that seems essential at the time. Should they take time to develop people or push products out the door? Or take time to develop people or encourage people to take time? Stop to do root cause analysis or patch the leak and keep on sailing? Even when such trade-offs don’t present themselves so explicitly, leaders are often stymied when they feel the need to narrow their focus and give up one aspect of lean practice to make progress on another.

But, lean practice is not about this question of “but” — lean is about the “and.” Frontiers AND fundamentals, for example. Tools and management. Technical and social. All are yoked together at the workplace. Fortunately, there are some encouraging trends regarding how people are talking about lean as a complete business system. For example, a new book, The Lean Turnaround, by veteran CEO and lean legend Art Byrne sheds light on leading lean as an integrative role. By sharing how he has led the introduction of lean practice in more than 30 companies (including the famed tale of transforming Wiremold), Art shares his view of how lean operates as a complete business system — a comprehensive way of leading (and managing).

From doing lean to being lean — it’s a system

Art’s book is a timely reminder emphasizing how lean operates as a complete business system. First, where you start and with which tool you use first depends on where you are and what your problem is. However, once you start, you find that everything must change — become lean — for any improvements to take root and generate further gains. For example, reducing inventory and boosting flow will force your sales force to rethink its opportunities and incentives; and will cause your accounting system to throw out standard assumptions about what to value.

As Art says, “Lean cannot be just one of 10 elements of your strategy. It must be the foundational core of everything you are trying to do; that is how it becomes your culture. Don’t just do Lean; be Lean.” Embrace lean thinking to solve business problems and make things better for your customers.

Lean cannot be just one of 10 elements of your strategy. It must be the foundational core of everything you are trying to do …

— Art Byrne, Author and Former CEO

This approach reinforces a belief of mine about lean leadership — that many of the cries for “strong leadership” are misguided. What’s needed today are NOT heroic figures who make great inspiring speeches. The essence of lean leadership is not who the leader is and what image he or she projects; the issue concerns what leadership practice accomplishes the organization’s aim and ultimate purpose. Any system that relies too heavily on charismatic “leadership” is inherently fragile and too dependent on the individual who happens to be in charge.

The real issue is how leadership builds systems that are the operational result of disciplined lean practice; that is, a problem-solving culture that creates continuous improvement that delivers business results while always solving customer problems.

You cannot separate management or leadership from work, the tasks of the value-creating work of the business. Lean starts (and eventually starts again) with the fundamentals of how you work at a micro-level detail. You can’t, as many theorize, separate leadership in some abstract notion from that place of work. Leadership is integrated into the work and not overlaid on it. And yet many prevailing conceptions of leadership fail to grasp this simple but essential truth.

On the Shop Floor: Saving Half a Second at Herman Miller

Recently, I was able to observe operations at a Michigan factory of Herman Miller and was excited by what I saw from the team that has been practicing lean thinking for 15 years. The team I observed was assembling the famous Aeron office chair. I saw a vibrant example of a problem-solving culture characterized by individuals who have a clear line of sight to the goals of the business, deep knowledge of the work and how lean practice applies to improving it, and enthusiasm that is sky-high — all of which leads to a very successful business and ultimately delighted customers.

The team was working enthusiastically to shave a half-second from their work cycle to meet the takt time of … 17 seconds. The team was working with its facilitator/leader in a thoughtful set of experiments to save that half-second. The team facilitators were working hand-in-hand with the operators, providing expert coaching to help them think of new ideas right there at the moment at the gemba.

Any observant visitor could see how this kaizen mind started at this micro level of work and extended throughout the plant. The material handlers were working at a pitch that was ten times the takt time, making their delivery rounds precisely every 170 seconds. Line-side inventory was minimal — if they are ever late, the line will stop because the workers will have no parts. They used a nearby yamazumi board for weekly reallocation of work elements they were improving daily — just like they write in the textbooks — except better.

Did I mention that the team was working to save half a second?

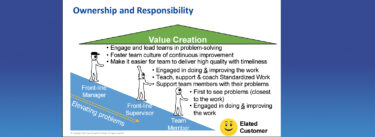

But what excited me most about this hotbed of problem-solving was not merely the satisfaction one gets by observing people making tangible improvements in their immediate work. You could see how these engaged team players were thinking hard about sharing their gains with the upper levels. You could see that this attitude was a deeply ingrained part of the culture — that leaders were guiding this focus on improvement to strengthen the capability of the overall plant and that they were getting each person to take the initiative to improve in alignment with company objectives.

And this represented the essence of transformational leadership for me: these team leaders (in their words) were not, ultimately, solving problems — but developing problem solvers. And they did so not through a blind trust, or by giving orders, or fixing defects: they did so through a mindful presence at the gemba, which developed the skills and capabilities of their team.

This type of leadership takes place best when you know the work itself. And such an approach contrasts sharply with many prevailing views of leadership.

Defining Lean leadership

Lean leadership focuses on creating a problem-solving culture where each member is engaged as an entrepreneurial owner of his or her challenges — shaving off half a second, reducing work-in-process, or making injuries a thing of the past.

At issue is the role of leadership in attaining the ideal lean enterprise. What role does leadership play in the creation of the system? How do you achieve that? Leadership has a dynamic role that should adapt to different circumstances, depending on the problem to be solved. Art Byrne describes the role of leadership in establishing a complete enterprise and the sometimes dramatic action required to do that.

The Herman Miller example demonstrates the actualization of problem-solving culture comprised of relentless lean practice. Above all, the objective should be to establish a system that is not dependent on any individual. As the organization matures, the role and behaviors of the leaders may change, as do the problems and challenges themselves.

Editor’s Note: This Lean Post is an updated version of an article published on December 13, 2012, one of the most popular posts about this vital lean practice.

Having read “Encouraging Signs on Lean Leadership” on lean.org, I found it to be an insightful piece that highlights the importance of strong leadership in promoting a culture of continuous improvement within an organization. The article’s emphasis on the need for leaders to lead by example and to create an environment where experimentation and learning are encouraged was particularly noteworthy. Overall, a great read for anyone interested in developing their leadership skills in a lean environment.

The “Peter Principle” is a major barrier to improved leadership.

This article heading says “Executive Leadership.” In the 10 years since this article was first published, three critical deficiencies have become even more clear and have yet to be overcome by anything more than a few CEOs.

1. To to coach effectively, executive leadership must have a great understanding of Lean. As we have all learned over the decades, most executives are not interested in obtaining the requisite knowledge from practice.

2. Like coaching, most executives are not interested systems thinking.

3. After some 25 years of calling Lean a corporate strategy, hardly any CEOs have bought into that idea. Overall, we can confidently say that they disagree that Lean is a corporate strategy.

Ten years ago we did not understand why this was the case. But today, we do understand. That should lead to some practical countermeasures — assuming there is a willingness to learn and improve.

Ten years ago article and still valid today.

Thanks for sharing