Recently I have heard from several members of the Lean Community wanting to know how to evaluate the lean efforts of their company. “How do we know how lean we are?” “What metrics should we use to measure our progress?” “Are we ‘world-class’ in terms of lean?” (Whatever ‘world-class’ is!) Because I’ve been getting calls of this type for years, and they seem to keep coming, let me share my answer.

I always start by asking about business purpose: What do your customers want that you are not currently able to supply? Lower price (which is currently impossible because your costs are too high)? Better quality? More rapid response to orders? Better support once the product is delivered? A better and faster quotation process? More robust and flexible product designs?

And what does your business need to prosper? Higher margins? The ability rapidly to exploit new opportunities in order to grow? A new way truly to solve customer problems and move into new markets?

Satisfy Your Customers and Help Your Business Prosper

Business purpose always has these two aspects — what you need to do better to satisfy your customers and what you need to do better to survive and prosper as a business. Fortunately, addressing the former issue often solves the latter, but you must know precisely what the problem is as you start.

For example, when I visited Jefferson Pilot’s policy writing operation for life insurance several years ago, managers were able to tell me immediately about their business purpose. It was to reduce the time needed to write a policy from 30 days to as little as one day. This benefited both the insured and the agents selling policies, who only get their commission once the policy is delivered to the customer. More to the point for the company, superior service would cause independent agents to select Jefferson Pilot as the preferred insurance to sell and permit JP to grow sales rapidly without cutting prices in an otherwise stagnant market.

Yet I’m often amazed that there seems to be little or no connection between current lean projects and any clearly identified business purpose. Set-up reduction is being pursued because it’s the right, lean thing to do. Pull systems are being installed because push is bad and pull is good. Meanwhile, customers are no happier, and the company is doing no better financially. So, start with business need, defined both for your customer and your company, and ask about the gap between where you are and where you need to be.

Customers, of course, only care about their specific product, not about the average of all your products. So it’s important to do this analysis by product families for specific products, summarizing the gaps in business needs your lean efforts must address.

With a simple statement of business purpose in hand, it’s time to assess the process providing the value the customer is seeking. A process, as I use this term, is simply a value stream — all of the actions required to go from start to finish in responding to a customer, plus the information controlling these actions. Remember that all value is the end result of some process and that processes can only produce what they are designed to produce — never something better and often something worse.

Tap Value-stream Maps to Assess Value

Value-stream maps of the current state are the most useful tool for evaluating the state of any process. They should show all of the steps in the process and ask whether each step is valuable, capable, available, adequate, and flexible. They should also show whether value flows smoothly from one step to the next at the pull of the customer after appropriate leveling of demand.

But please note that you must interpret the map in terms of business purpose. Not every step can be eliminated or fixed soon, and many steps may be fine for present conditions even if they aren’t completely lean. So work on the steps and issues that are relevant to the customer and the success of your business.

I know from personal experience how easy it is to get confused and pursue what might be called the voice of the lean professional rather than business purpose. When I was involved in a small bicycle company some years ago, we welded and assembled eight bikes a day, shipped once a day, and reordered parts once a day. (This was a revolutionary advance from the previous state of the company.) But I was determined to be leaner than even Toyota. I urged that we build bikes in the exact sequence that orders were received, often changing over from one model to the next in a sequence of ABABCBAB.

This approach was deeply satisfying. But we only shipped and ordered once a day! The sequence AAABBBBC would have served our customers and our suppliers equally well and saved us five changeovers daily, requiring the human effort we badly needed for other purposes.

Does every important process in your company have someone responsible for continually evaluating that value stream in terms of business purpose?

I had a similar experience when I visited a company that had reduced set-up time on a massive machine — from eight hours to five minutes. A big kaizen burst had been written on the current-state map next to this high set-up time step, and a dramatic reduction seemed like a worthy goal to the improvement team. However, when I asked a few questions, it developed that the machine only worked on a single part number and would never work on more than a single part number! Set-up reduction on this machine — to reduce changeover times between part numbers — was completely irrelevant to any business purpose, no matter how “lean” a five-minute set-up sounded in theory. The lean team justified their course of action by pointing out how technically challenging the set-up reduction had been and how much everyone had learned for application in future projects. But that’s exactly what I had thought at the bike company, where every penny counted to support the current needs of the business. I’m now older and wiser.

Factor the Human Element Into Your Lean Work

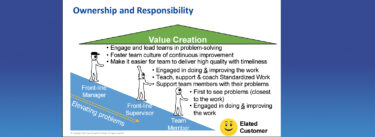

Brilliant processes addressing business purpose don’t just happen. They are created by teams led by some responsible person. And they are operated on a continuing basis by larger teams led by value-stream managers. So the next question to ask is about people: Does every important process in your company have someone responsible for continually evaluating that value stream in terms of business purpose? Is everyone touching the value stream engaged actively in operating it correctly and continually improving it to better address business purposes?

My formula for evaluating your lean efforts is therefore very simple: Examine your purpose, then your process, then your people. Note that this is completely different from the multiple “metrics” that members of the Lean Community often ask for: How many kaizen have been done? How much has lead time been reduced? How much inventory has been eliminated? And how do all of these compare with competitors or even with Toyota?

Good performance on any or all of these “lean” metrics may be a worthy goal, but turning them into abstract measures of “leanness” without reference to business purpose is a big mistake. At best, they are functional measures for the lean improvement function. What’s really needed is business measures for every value stream, measures developed and widely shared by a responsible value-stream leader and understood and supported by the entire value-stream team.

Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX)

A continuing education service offering the latest in lean leadership and management.

Understanding the issue of business benefit but there are other considerations. At an offshore company, we integrated changeover between sizes of products to make one at a time, but the company still ordered in thousands. The thing is, when we moved from one building to the next, we allowed them to start with bigger batches but the operators and supervisors liked the one-at-a-time method as being easier to manage and find problems. Scale makes a difference?