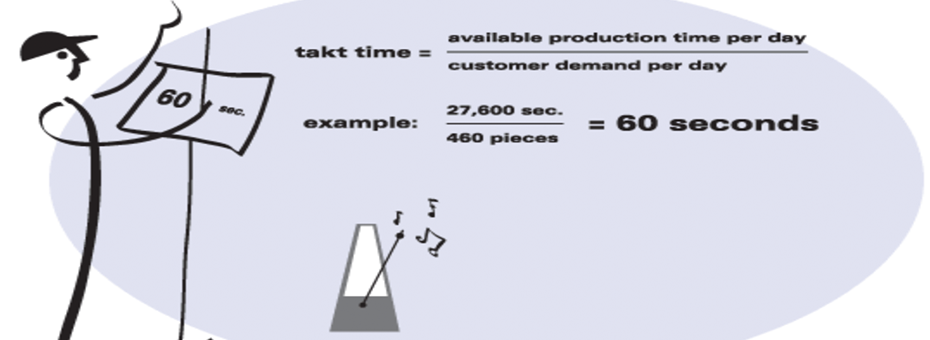

Let’s start by first defining what takt time is. The word takt is the German word for the baton that the orchestra conductor uses to regulate the tempo of the music. It in effect is the beat of the music. In lean, takt time is the rate at which finished product needs to be completed in order to meet customer demand. Mathmatically, takt time is derived by dividing the time available by the customer demand. For example, if there are 450 minutes in a work day and the customer demand is for 450 units a day, then 450 minutes/ 450 units = a 60 second takt time. If the time available stays the same but demand doubles, then the takt time would be cut in half, 450 minutes/ 900 units = a takt time of 30 seconds.

This is not a concept that exists in a traditional batch focused manufacturing operation. You won’t see it anywhere because the approach is totally different. Product there is generally made to a forecast in anticipation of customer demand. As a result, when companies think about making the conversion to lean, takt time is probably one of the last things they may think about. They are much more likely to focus on “flow” and “pull” when they think about converting to lean.

While most people easily grasp the lean concepts of “flow” and “pull,” working in these conditions is one of the more challenging barriers to becoming lean. Most traditional companies manufacture in a batch, and understand that moving to producing in flow (in fact in a “one piece flow”) is a vastly different approach from what they are doing. It is so radical in fact that many companies reject this out of hand as something that seems impossible to do. They might have (and have always had) 2-4 hour changeover times on all of their equipment and are convinced that there is nothing more that they can do about this—and so they will always have to produce in a batch. And as long as this belief persists they are right: moving to flow production is out of the question.

The idea of pull, which results from the incoming demands of customers, might be easier to grasp for the traditional company. They typically follow batch production, which is usually based on a push scheduling system driven by an MRP program, and some form of sales forecasting system. Their sales forecast anticipates customer demand, which is fine, but production is then pushed through the system in the hopes that the forecast is right and that product will be available in the right quantities when needed. This totally separates production from the customer, and causes all kinds of unnecessary effort when the forecast is wrong, which is most of the time by the way, and operations has scramble madly to catch up. As a result, it is often easier for a traditional company to implement some form of kanban or pull system to tackle this problem. Instead of focusing on reducing setup times, they will simply put kanban cards on their batches, hoping to connect the customer more directly to production and reduce the problems created by the forecast errors. This may in fact help but the gains will be limited.

The concept and importance of takt time, on the other hand, is a little more difficult for most traditionally managed companies to grasp. This is unfortunate, because to me takt time is the most important of the four “Lean Fundamentals” that are the basis of any lean turnaround.

Let’s start by listing what are commonly thought of as the four lean fundamentals:

WORK TO TAKT TIME

ONE PIECE FLOW

STANDARD WORK

PULL SYSTEM

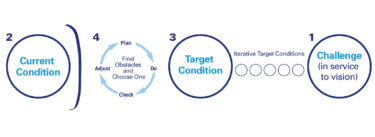

When you start a lean turnaround it is important to understand that you are really trying to change from your current approach to one where all of these conditions are present. Is everything working to takt time? Is everything in a one-piece flow? Do we have standard work in place everywhere and is it being followed? And finally, do we have pull systems in place from the customer all the way back to our vendors and maybe even their raw material suppliers? When your company can answer yes, every day, to these four questions, then congratulations, you are making great progress on your lean turnaround.

They are all important but notice which one always comes first: “WORK TO TAKT TIME.” Why is that? To me it is because it is the basis from which everything else flows. Takt time represents the beat of the customer, or, the rate of demand. As the primary focus of the lean company is delivering more value to its customers than its competitors can then conformity to their demands in a quick, efficient way is the main driver. Takt time is therefore what sets the tone for everything else. The traditional batch company produces under the theory of “sell one, make 10,000” while the lean company is always striving for the lean ideal of “sell one, make one.” Takt time is what informs us what the “sell one, make one” rate should be.

Whenever you start a kaizen activity the first question should always be, “What is the takt time?” The answer to this in effect tells you what you are trying to do here. If the demand, for example, is 100 a day, you don’t want to be making product at the rate of 1,000 per day, even if you can. And the concept of “even if you can” is very important here. This is particularly true when it comes to new product introductions. It is not uncommon to see a traditional batch company overestimate the demand for a new product, spend lots of time and money building an automated machine that can make 5,000 per day, build up six months of inventory in advance at that rate, and then find that the demand turned out to only be 200 per day. A huge waste. The lean company, looking at takt time, can start small: simple bench top equipment might allow it to make 100 per day to start and then see how demand develops. If it winds up at 200 per day, adding a second shift of a second bench top line will solve the problem without the waste. It’s always better to scramble to keep up with demand than to be way out in front building lots of product you may never sell.

The most important gains from takt time, however, come when you add the word work, as in “Work to takt time.” This is an approach that doesn’t exist in a traditional batch company that produces to a forecast where the main thrust is: “make the number.” It could be a daily or weekly number of parts, but more often it is a monthly goal. Everything is tracked on a computer somewhere but it is difficult to see where you stand by walking on the shop floor. The equipment is arranged in functional departments by type of equipment so even if you knew that department A was making its number it wouldn’t tell you much about where the final product stood as Department A only makes one of the components.

Work to takt time on the other hand not only provides the rate needed to meet customer demand; it also provides the discipline that is needed for lean. When you set up a new cell to produce a product complete from raw material to in-the-box, this sequence will all be based on the takt time, i.e. the time available/number of units required. You are trying to make the cycle time equal the takt time. This means that you have to make the takt time hour by hour as there is no time to make up for lost output. This creates significant pressure and requires tremendous discipline. You would never set up a new cell with excess capacity, for example, so making the required number hour by hour is very critical.

At the same time, setting up a new cell according to takt time also creates an opportunity for simple visual control boards on the shop floor that can tell you, and more importantly, the operators in the cell, where they stand on meeting the customer demand. Everyone knows that they are no longer just making to a forecast; instead they are responding to the customer. In this way takt time in effect brings the customer directly to the shop floor. Everyone can see if the customer demand is being met without any attempt to make more than the customer requires. Sell one, make one. In addition, it helps build great teamwork as the importance of meeting takt time (i.e. serving the customer) is clear.

Setting up a cell or process to perform to takt time is one thing. Getting it to run consistently at the takt time is the real challenge. Vendor quality problems, late starts, machine breakdowns, and many other challenges will occur. This is where the discipline comes in. The hourly production control boards at each cell will highlight the issues. Daily management is needed to create countermeasures and get back on track. “Work to takt time” is a tough task master but it will drive all the other things needed to become a lean enterprise.

SUMMARY

Becoming a lean enterprise takes enormous time and effort. Establishing and maintaining the four lean fundamentals requires leadership, discipline, and the involvement and contribution of every associate. You must understand that lean is strategic—and not some new cost reduction program. Having said all that, the lean fundamental of “work to takt time” is the driving force that ties everything together. As you strive to get to the lean ideal of “sell one, make one,” takt time will define what that means. Always start with the question: “What is the takt time?”