Recently, I’ve noticed some confusion about the relationship between the Toyota Way and Toyota Kata. So, with the publication of the second edition of my book, The Toyota Way, I want to clarify the differences.

The Toyota Way and Toyota Kata are management concepts described in well-known books that reveal the thinking and practices underlying the company’s success. The Toyota Way summarizes the management system Toyota has evolved over the last century as a set of fourteen principles. Toyota Kata describes the practice routines Mike Rother developed to aid people in getting started developing the habit of scientific thinking he saw as central to Toyota’s success.

The term “scientific thinking” can be confusing and might spark the picture of a lone scientist sitting in the lab conducting some fundamental research and developing abstract models. However, in lean management and problem-solving, scientific thinking refers to the mindset and practices that enable people to achieve challenging goals. In teaching and coaching scientific thinking, lean practitioners, then, are trying to develop people’s “practical scientific thinking” skills, which will help enhance their problem-solving capabilities.

These were written about in different books and are often practiced as though they are different schools of thought or approaches to lean transformation. So the question is: Are these two systems compatible, or do we have to choose to believe in one or the other?

I have had an insider seat to both since I have been studying Toyota for about 40 years, and Mike was my graduate student at the University of Michigan and lives close by. So we regularly have long discussions about these topics.

My overall conclusion is that while I was deriving general management principles from my learning about Toyota, Mike was delving into a practical approach to one of the core aspects — problem-solving through scientific thinking.

Mike’s model of scientific thinking — the Improvement Kata Pattern — was derived from watching some of the best Toyota Production System (TPS) masters in Toyota at work. He then went beyond the conceptual model to help others learn how to do this themselves through an age-old approach to mastering complex skills — deliberate practice with a coach!

Integrating The Toyota Way and Toyota Kata

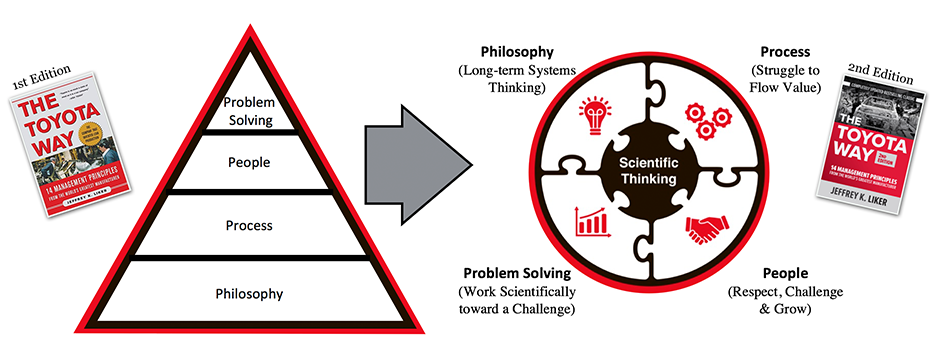

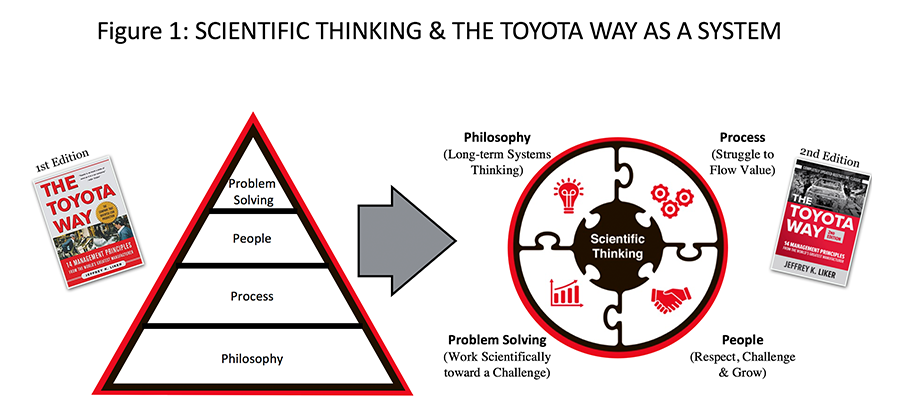

Based on my long discussions with Mike and some soul-searching myself as to where this all fits together, I changed the foundational 4P model of The Toyota Way to place scientific thinking in the center (see illustration below).

In the first edition published in 2004, I had represented the model as a pyramid, placing philosophy as the foundation and problem-solving at the pinnacle. At that time, it had seemed that scientific thinking should be a part of problem-solving. However, after thinking more about it, I made two significant changes to the model for the 2020 second edition:

- I changed the model to a set of interconnected puzzle pieces to show that all the components are interrelated — a system.

- I put scientific thinking at the system’s center after concluding that all the principles are more effective with a scientific approach. For example, though the process principles seem to lead to a straightforward implementation of tools, like a work cell, they don’t. Instead, with a scientific approach, you start with a vision or objective, such as achieving one-piece flow of value to customers. You then experiment with ways to work toward this vision, continually learning and refining your process.

Seeing Scientific Thinking in the TPS

While “scientific thinking” may seem new and perhaps theoretical, it is consistent with Toyota’s teachings, going back to the first TPS manual by Taiichi Ohno: “On the shop floor, it is important to start with the actual phenomenon and search for the root cause in order to solve the problem. In other words, we must emphasize getting the facts.”

One of Ohno’s students, Hajime Ohba, later explained in a public presentation: “TPS is built on the scientific way of thinking … How do I respond to this problem? Not a toolbox. [You have to be] willing to start small, learn through trial and error.”

In his excellent 2004 Harvard Business Review article on “Learning to Lead at Toyota,” Steven Spear discusses the rigor with which Toyota trains all its managers to be scientific thinkers: “Trainees watch employees work and machines operate, looking for visible problems… Learners articulate their hypotheses about changes’ potential impact, then use experiments to test their hypotheses. They explain gaps between predicted and actual results… Supervisors act as coaches, not problem solvers. They teach trainees to observe and experiment.”

Compare this with Rother’s description of the basics of practical scientific thinking for the rest of us who are not PhD scientists:

- Acknowledging that our comprehension is always incomplete and possibly wrong.

- Assuming that answers will be found by testing rather than just deliberation.

- Appreciating that differences between what we predict will happen and what actually happens can be a useful source of learning and corrective adjustment.

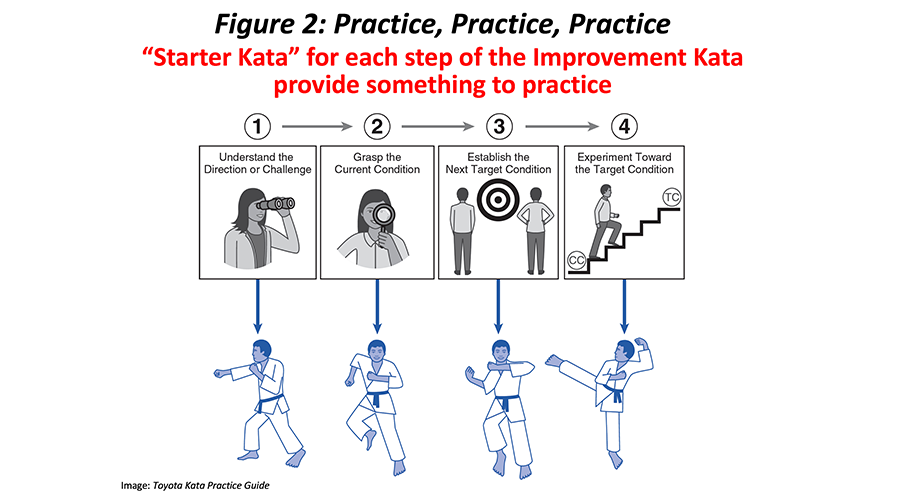

Developing the Kata

Mike wanted to go beyond elucidating principles of scientific thinking, so he arrived at the approach of daily practice via kata. Kata in Japanese martial arts like karate are specific movements that the master teaches to the learner through demonstration and then watching the learner try, repeatedly, until the student achieves some level of mastery of that specific, building-block skill. This approach then leads to mastering the next kata, and next, and so on. Over time, the karate student moves from practicing individual kata to combining them as situationally demanded when fighting. Those who have seen The Karate Kid have seen kata in practice; those who have watched a jazz band play have seen the results.

Those who have seen The Karate Kid have seen kata in practice; those who have watched a jazz band play have seen the results.

Mike provided us with the Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata — including a set of practice routines, or “Starter Kata,” for each stage of the model, which people can use to practice scientific thinking deliberately.

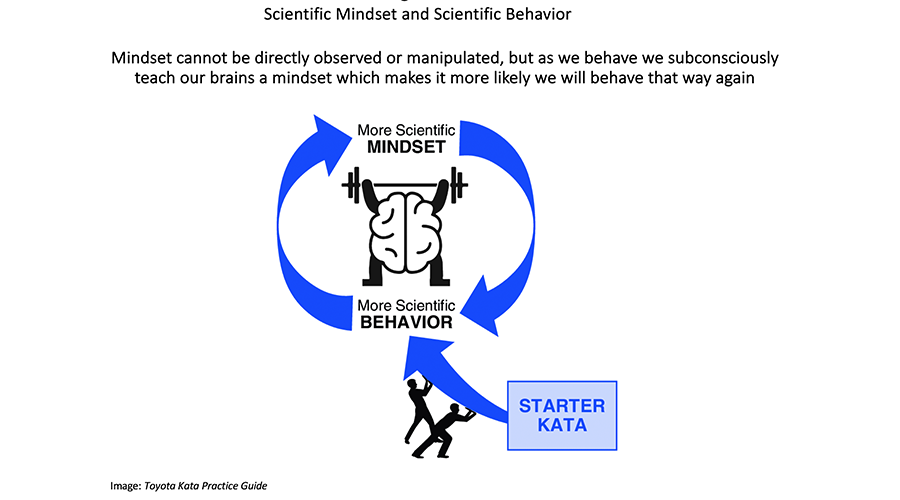

Having a way to practice scientific thinking is critical to counter our natural “problem-solving” instincts. All of our skills and ways of thinking occur in our brains. Routine actions like maneuvering our car are bundles of connected neurons that we can call up, somewhat like computers call up subroutines. However, the problem is our natural subroutines for solving problems program us to quickly imagine solutions before deliberately thinking through the problem definition and understanding the current condition.

The Lean Community has offered various methods to prevent this jumping-to-conclusions instinct, such as systematically stepping through the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) process. However, neither telling people to do this nor several-day problem-solving workshops are enough to create new, counter-intuitive neural circuits.

It is tempting to try to devise a way to flush our minds clean of these old thinking habits, but what is in our brain does not in any natural way get wiped as we can do to a computer’s memory. Instead, we must build new neurological structures that, when strengthened through practice, become our go-to for addressing problems. The old well-worn ways of fast thinking start to fade into the background since we do not use them, and the new slow-thinking patterns start feeling more natural. We are practicing, or should I say “deliberately practicing,” a new way and in doing so rewiring our brains.

Creating Daily Habits of Deliberate Practice

Toyota teaches practical scientific thinking to each manager, beginning when they are hired, and coaches reinforce the practice daily. But the rest of us need some regimen to practice deliberately. Mike’s Improvement Kata serves this purpose (See illustration below).

In total, the Improvement Kata starts with a clear purpose in the form of a measurable challenge, and then we iteratively learn our way to the challenge. The starting assumption is that we do not know how to meet the challenge because of too much uncertainty. So we have to step our way through it experiment by experiment, adjusting and learning as we go. Most people are uncomfortable not knowing, accepting uncertainty, and recognizing that the future is not predictable. Therefore, we need to practice our reactions when confronted with such situations, ideally with a coach.

The emphasis in Toyota is on learning by doing. Toyota values theory, but as a basis for developing practice through experimenting.

Now, we all know the emphasis in Toyota is on learning by doing. Toyota values theory but only as a basis for developing practice through experimenting. To make this scientific-thinking pattern gel in our minds, we need enough practice to create strong neural pathways.

Understanding the Neuroscience of Learning

We also know that there is a limit to how much new input our brains can absorb in one session, and it’s less than you might think. Twenty minutes seems to be about right. Practicing for short periods daily for several months is much more impactful than morning-to-night sessions that we might have in an executive immersion training course or a one-week kaizen event.

Neuroscientists have demonstrated that behavior and thinking are interconnected (see illustration below). When we do something, that information gets encoded as a bundle of neurons and synapses that connect the neurons. When we practice a particular way, we get a very efficient circuit that becomes our habit. So, for example, if we approach a problem through fast thinking, jumping to conclusions, we are more likely to address issues. To counter that tendency, we need to behave scientifically repeatedly, which will change how we think and make us more likely to approach problems that way in the future.

When you put this all together, you get the Improvement Kata model and its associated practice routines done in a coach-learner relationship. Toyota seems to do it naturally without a lot or scripting of how the coach teaches the student. Mike has made it explicit and more structured in Toyota Kata to help those who are not already in a mature organization with a culture of scientific thinking.

Does Toyota Kata Replace the Toyota Way?

Does this mean that Toyota Kata now replaces the Toyota Way since scientific thinking is at the center? Certainly not. The 4Ps of the Toyota way reflect a management system that is more than individual people thinking scientifically. It starts with a collective clarity of purpose and core values that guide the overall enterprise. What is the organization’s purpose? What is the collective vision for how we want the enterprise to operate? This system must be lived and modeled by all managers to become the guiding force of the culture.

The Toyota Way starts with a collective clarity of purpose and core values that guide the overall enterprise.

Philosophy does not emerge from experiments but needs to be carefully thought through and embraced to help provide direction to specific improvement efforts. Similarly for Process, there is a body of knowledge about lean processes and moving toward one-piece flow that you are not likely to discover through experimentation within a mass-production system. As a result, we need to develop people’s capabilities in many ways besides scientific thinking to get to the leadership and culture we desire. Problem-solving is best done with a scientific mindset and includes ways to align goals (hoshin kanri) toward a clear strategy for the products and services of the firm.

We should also recall that Mike calls these “starter kata” rather than “finishing kata.” So, he does not intend for people learning scientific thinking to continue forever to follow the “starter kata” precisely as if it were a new rigid method for problem-solving. Instead, they are for the student to practice — and develop — a scientific thinking mindset. Perhaps we can view the kata as a catalyst that juices scientific thinking, which, in turn, is the engine that drives the Toyota Way. Without it, or some equivalent way of developing people to think scientifically, the Toyota Way might remain at the level of principles without practice.

Editor’s Note: In case you missed it! This Lean Post is a lightly edited version of an article published in February 2021.

Improvement Kata/Coaching Kata

Develop Scientific Thinking, a Foundation of Lean Management in the 21st Century.