Two words — alignment and transparency — drive the lean transformation at Turner Construction Company, asserts Doug Cooper, the company’s vice president for Lean, Safety, and Active Caring, New York. The international heavy construction company, which built such notable buildings as Times Square Tower and World Trade Center Tower 2, has used those words — practices really — to ensure everyone from the CEO to their frontline crews understands its strategic objectives and is motivated and able to help it achieve them.

Turner is a North America-based, international construction services company and is a leading builder in diverse market segments. The company has earned recognition for undertaking large, complex projects (such as Yankee Stadium, shown above), fostering innovation, embracing emerging technologies, and making a difference for their clients, employees and community.

With a staff of 10,000 employees, the company completes $15 billion of construction on 1,500 projects each year. Turner offers clients the accessibility and support of a local firm with the stability and resources of a multi-national organization.

Taking that goal to heart, the company’s New York Business Unit (NYBU), where Cooper is based, launched the effort to adopt lean thinking in 2014. In 2017, the unit started a Co-Learning Partnership with the Lean Enterprise Institute, which eventually, in 2018, included having the group’s leaders participate in LEI’s Lean Leader Program. The program introduces executive leadership teams to A3 thinking and practices through hands-on learning (the participant tackles a current business problem using the

A3 process).

Simultaneously, the group executed workplace improvement projects and developed an internal lean team that gained valuable capability through hands-on practice.

By 2019, with these early lean transformation efforts paying off, the NYBU leaders set out to create a continuously improving management system built on hoshin kanri, an approach to set, plan, and execute on strategic direction, and A3 management and problem-solving practices.

Creating a Competitive Advantage

Like many companies developing a new strategy, Turner was seeking a way to differentiate itself from competitors and achieve its vision — in its case, to be the No. 1 provider of construction and technical services globally. The company leaders had decided to adopt lean when they “realized that we had to become agile, and we had to be our own worst critics and really look at our processes and understand that we could improve them,” Cooper says. “And we wanted to make sure we focused on realizing our vision.”

The leadership team felt that lean management, with its focus on the behavior of leaders, would be both that differentiator and a way to align everyone in the company toward achieving the vision. For example, Cooper notes that lean leaders are problem-solvers; they don’t react with knee-jerk responses that ultimately fail to resolve issues. Instead, they work with their teams to identify and solve the root cause of problems, so they’re not solving the same problems repeatedly. Adopting those and other lean behaviors and creating a structure that supported them “was something we felt would be that differentiator,”

he says.

Turner’s Lean Journey

As critical, the leaders realized that it was their job to help their staff understand how their work processes — and improvements — would help the company achieve its strategic objectives. “We talked about motivation, about making sure that people at the point closest to the work are connected with strategic planning,” Cooper explains. “So, when we began our journey with LEI, we wanted to begin building commitment around lean practices. We didn’t want to be just a construction company that was trying to be lean; we wanted to be a lean enterprise that also did construction.”

Laying the Groundwork for Change

At the New York business unit (NYBU), leadership realized that the change must start with them, reasoning that if the leaders didn’t follow — and model — the new processes, they couldn’t expect their staff to adopt them. So, for the first step, the leadership team worked to build their A3 problem-solving capability with the help of LEI coaching and executive workshops. Then, the leaders at each level cascaded the training through each level of the organization to the frontline staff. Additionally, as they developed A3 problem-solving capability throughout the ranks, they encouraged everyone to take the time to solve problems in their work processes.

We didn’t want to be just a construction company that was trying to be lean; we wanted to be a lean enterprise that also did construction.

— Doug Cooper

During fast-paced construction projects, strict timelines leave little room for identifying and solving the root cause(s) of problems — and missed deadlines often come with negative consequences. “We wanted to let them know that they could take that pause and honor that structure to be able to do A3 problem-solving, to use lean thinking in addressing problems and in a fact-based structure,” Cooper explains. He adds that the leadership team felt that team commitment to lean thinking and practices and contributing to corporate objectives would grow as they became more engaged in improving their work.

Once momentum for problem-solving was underway, NYBU leaders directed their attention to strategic planning and, unexpectedly, solving a problem of their own. To determine its current state, the company leaders had gathered the unit’s five general managers together and asked them to write down the strategic priorities for the business unit for the previous year. The seemingly straightforward exercise delivered a gut punch: each leader had a different vision in mind and, presumably, were diligently working toward it, which exposed that, like many companies, strategy execution was a sticking point. More specifically, Cooper notes, we realized: “how can we expect our line staff to be aligned with strategic priorities of the company if the senior leadership with a business unit of the company is not aligned?”

That insight caused the business unit leaders to conclude that “for our future state, we wanted to create clear alignment in communications of the strategic plan and vision from the president and CEO of the company to our line staff,” Cooper recalls. “And we would measure that [by whether] a priority issued by the CEO or the executive committee made it through the leadership.” He adds that the true measure of success would be whether a plumber, carpenter, or electrician on a job site could demonstrate through their work that they knew of the company objectives and how they were expected to contribute.

At the same time, Cooper added, business unit leaders wanted to continue empowering the people closest to the work to have the capability to identify and solve problems.

Combining Hoshin Kanri and A3 Management

Creating the Management System

The New York leaders decided to adopt hoshin kanri as its approach to strategy deployment and work to “stitch that together” with the problem-solving practices into a management system.

So, with its first hoshin, Turner New York sought “to create a structure that would allow us to honor our strategic priorities, which at the time was to create the right [work] environment,” Cooper explains. “We wanted to make sure we had the full engagement with all of our employees, all of our team members, all of our trade partners. We wanted to continue to create that lean culture that exhibited the behaviors that we were looking for — continuous improvement, problem-solving, and respect for each other and people we come in contact with — and that we work every day to take that closest to where the work is being done.”

We wanted to continue to create that lean culture that exhibited the behaviors that we were looking for — continuous improvement, problem-solving, and respect for each other and people we come in contact with — and that we work every day to take that closest to where the work is being done.

— Doug Cooper

Turner’s NYBU leaders translated the broad corporate-level goal of “Creating the Right Environment” into a business-unit goal to achieve rigorous alignment in the communication of the strategic plan and vision from the company president and CEO to their frontline staff.

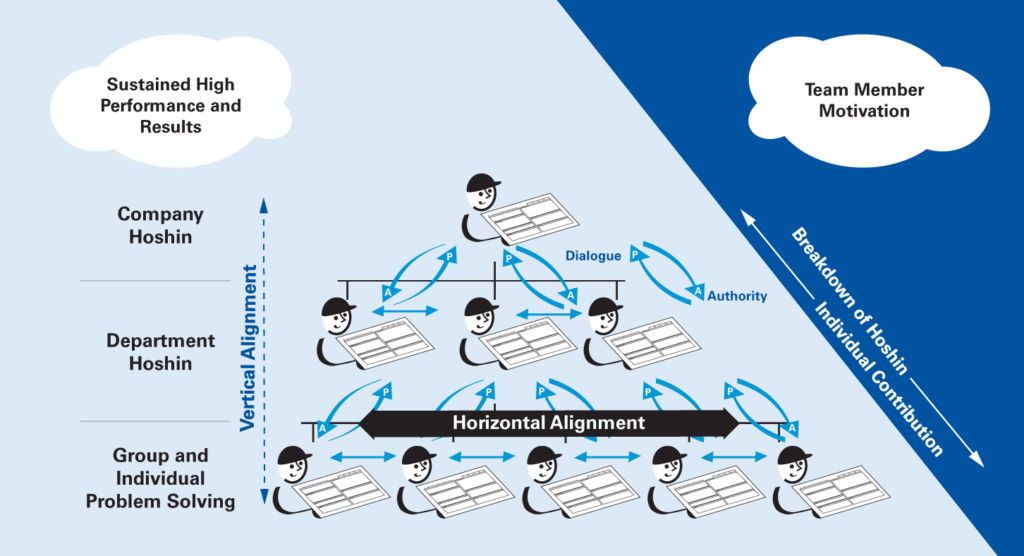

Cooper explains that Turner’s executive leadership hoshin (strategic plan) sets “broad and aspirational” enterprise goals. Then, leaders at each level — senior vice presidents, general managers, and department heads — create hoshin plans specific to their area of responsibility, including objectives and specific activities, that help the company achieve its company-wide objectives.

“It’s like a funnel,” Cooper says. “You’re taking those broad-based strategic priorities, and the idea is to [at each level of the organization] attach some objectives, activities, targets, and measures that could be implemented to move the ball toward achieving that goal.” With this approach, Turner creates a continuum where frontline tactical objectives support corporate-level strategic ones. Also, the four types of problems are addressed appropriately, handled by those closest to the customers impacted by the issue, with support from others as needed.

“Through that funnel, we’re getting to very finite points — a very narrow and deep consideration of singular problems that can be solved at the job site, the final level, through the use of A3 thinking and problem-solving,” Cooper explains.

Understanding the Importance of Alignment and Transparency

At first glance, Turner’s management structure may not seem much different from traditional management, but it is. Though Turner’s organizational chart appears to be a conventional hierarchy, the company’s leadership practices are fundamentally different. Significantly, management decisions and communications flow not only top-down; they flow top-down and bottom-up. Leaders do not simply send a list of objectives to their direct reports. Instead, each level closely collaborates with the manager they report to and their direct reports to agree on priorities and targets, creating transparency and alignment.

Significantly, with hoshin kanri, “communications” means more than just the traditional approaches: the annual company-wide meeting presentations, newsletters, and the like. Instead, hoshin communication incorporates specific frequent leadership practices that consistently reinforce a focus on organization priorities while continually building everyone’s ability to improve their work processes. Within that framework, A3 management and problem-solving support efforts to remove obstacles or address issues that complicate everyone’s ability to do their part in helping the company achieve its vision.

Another crucial difference from the traditional strategic planning approach is that teams at the gemba — at the worksites closest to the customer — inform the hoshin. So, for example, Turner’s priorities — to create the right environment, achieve full engagement, promote a lean culture, and live injury-free every day — all aim to help frontline workers.

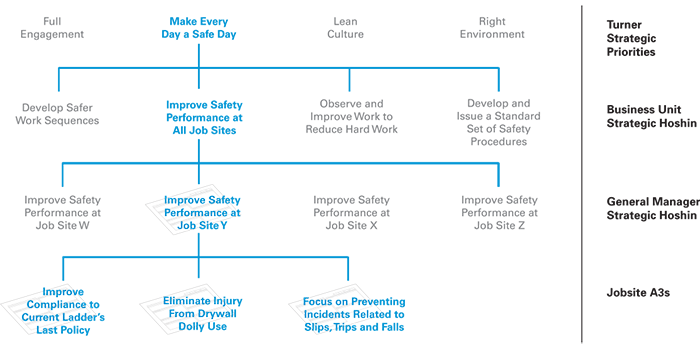

Cascade of Hoshin at Turner Construction

The hoshin, or strategic, plans, are developed at each level of the organization through top-down, bottom-up discussions that maintain alignment and transparency of the organization’s broad strategic objectives at every level. Such collaboration ensures everyone can focus their efforts on helping the organization achieve its objectives.

In Turner New York’s case, the senior vice president works with corporate leadership to whom he reports and the general managers to set the business unit’s hoshin, or strategic plan. In turn, each of the general managers works with their department heads to clarify the linkage of their work, ensuring it supports the business unit objectives. Then, the department heads develop and execute the GM-level hoshin, working with their frontline staff to identify and resolve specific problems through structured problem-solving (A3). As a result, leaders at each level align their teams to participate in explicit activities that move the company closer to achieving a strategic objective.

Supporting this organizational structure is a small group of leaders who advise and coach lean practices. For example, a regional lean manager (RLM) helps the senior vice president create and manage the top-down, bottom-up management system. The RLM also facilitates the general managers’ efforts to develop and execute the business-unit-level hoshin with their leadership teams. An LEI Coach supports the RLM and coaches everyone on the management process, which combines hoshin kanri and A3 thinking and practices.

With this organizational structure, “We have consistency, [a plan] that’s driven from the top of the organization through the general managers to their leadership teams and, ultimately, problem-solving at the project level,” Cooper explains.

A cadence of monthly meetings, where each level reviews and reports progress, maintains strong alignment and focus on the business unit’s — and the company’s — top objectives. Turner New York has experimented with various meeting cadences, but, currently, the meetings are held January through October, when next year’s hoshin planning commences.

“When we have these meetings, we talk about those A3s — about the problems we’re trying to solve,” Cooper explains. “And problems are not something that’s dreaded within the organization; they are opportunities for us to improve,” he asserts. “They are opportunities for us to challenge our current systems and standards, to ask really, really good probing questions, and to be able to learn collectively and socialize that learning out to the organization.”

Improving Safety Performance

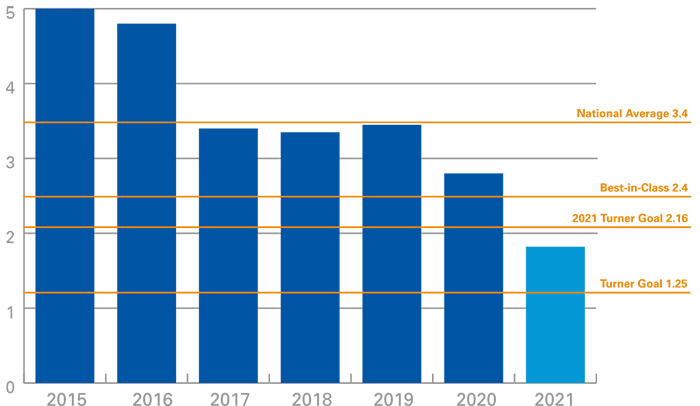

A closer look into one of the business unit’s objectives demonstrates how Turner maintains this top-down, bottom-up alignment. Another of Turner’s strategic priorities is “Living Injury-Free Every Day,” which emerged in response to the problem at the gemba. Tradespeople were getting hurt. (Recall that at the “top-of-the-funnel,” these goals are aspirational.) As the goals and plans are translated at each level, from corporate to job sites, they become increasingly specific, often targeted to a particular construction project. Cooper explains that as they become more precise, using A3 problem-solving, the goals become more actionable and measurable. For example, translating “Living Injury-Free” from the corporate to the business-unit level, the New York SVP and Cooper set a goal to achieve zero on-the-job injuries by improving the situational awareness of everyone entering job sites. In turn, the GMs, working with the SVP and Cooper, set safety-related tactical objectives, deciding to have the frontline crew focus on reinforcing its “Ladders Last” policy and “A-frame Cart” guidelines, among other efforts.

“We were very specific, very purposeful” in choosing projects because, as someone once said, ‘a problem well-stated is a problem half-solved,’” Cooper notes. Once stated, specific activities and countermeasures are taken to resolve the problems by achieving a specific target. The process of selecting projects, setting targets, and determining actions to achieve them is guided by the discipline of A3 problem-solving.

Problems are not something that’s dreaded within the organization; they are opportunities for us to improve.

— Doug Cooper

Turner had implemented “Ladders Last” in May 2011, and the policy had significantly reduced the business unit’s ladder-related safety incidents. However, current data indicated that incidents had started to rise. So, using A3 problem-solving, the team dug into more detailed project data, discovering that project crews were not following the policy consistently for various reasons, including that many didn’t fully understand the policy or its importance to the company. As a result, they weren’t holding themselves accountable to enforce the policy or communicate it to the subcontractors. To address this, “we provided additional training that would consistently build understanding among the team about why the policy is important and make clear that ‘Ladders Last does not mean ladders no,’” Cooper says. Then they set specific measures to track progress and a cadence for follow-ups.

New York Business Unit Records Incident Rates

The New York Business Unit leaders credit improvements in its primary safety measure to their new management system, with hoshin kanri practices keeping everyone focused on safety goals and

A3 problem-solving identifying and resolving unsafe situations.

The “A-frame Cart” A3 called for reducing injuries caused by the use of drywall carts, where “we found that we had in excess of over 200 incidents relating to this particular conveyance system,” Cooper says. Further investigation identified when and how cart-related injuries occurred, prompting the team to implement specific countermeasures that crews should take to avoid those situations. “So that resulted in some countermeasures of socializing the hazards that are related to [these carts], about how to safely utilize them,” Cooper explains. He adds that the business unit shared the countermeasures company-wide and, “as a result, we’ve seen a decrease in the number of A-frame cart-related incidents.”

Cooper notes that, taken individually, the results of the frontline A3s don’t achieve 100% of the business unit’s safety goals or corporate’s strategic priority, but they contribute to doing so. “These two A3s, the A-frame Cart and the Ladders Last, improve[d] our performance as related to our ‘building life’ program,” he says.” Further, within a management system where dozens of these tactical frontline efforts are in process, the combined results ultimately help the business unit and the company meet their strategic priorities.

Understanding the Broader Benefits

Achieving goals and objectives of any sort are significant wins, but for Turner’s NYBU leaders, more critical is the progress the group has made toward building a system that creates and supports transparency and alignment. “Now, we’re solving new problems and have more people using the [problem-solving] structure [of A3s],” Cooper says. “We are using the structure for incident and near-miss review, and we’re holding ourselves accountable for really digging into the root cause of the issues as it relates to what’s happening in our jobs.”

Though Turner can’t claim yet to be a lean company that does construction, Cooper asserts, “we’re working diligently and intentionally toward that goal, and we’re beginning to see fostered commitment to it.”

As for whether practicing lean has created a competitive advantage, Cooper can’t site specific proof. However, he notes: “We’ve had a number of clients that we do a lot of work with say that they respected and appreciated what we’ve been doing.”

“As a matter of fact, recently, we had a client ask us to provide a proposal for a project, and rather than giving them that onerous three-ring binder proposal, they wanted it in an A3 format,” he adds. “They wanted to see what their project would look like as an A3 — there were certain processes, certain problems that they wanted us to address in that fact-based problem-solving structure. So yes, in short, I think lean has a lot to do with what differentiates us.”

Hoshin Kanri

Aligning and Executing on Your Organizational Objectives.

The Turner Construction Company really caught my attention when Doug Cooper said, “We didn’t want to be just a construction company that was trying to be lean; we wanted to be a lean enterprise that also did construction.” This showed me that this company takes pride in figuring out the process before starting the job. I found it very interesting that Turner has been in some big projects such as the Times Square Tower, World Trade Center Tower 2, and Yankee Stadium. Another thing that stood out to me was the positive mindset that Turner carries with them and how Doug said that, “problems are not something that’s dreaded within the organization; they are opportunities for us to improve.” Very helpful.

Glad you took that away, Thomas. Turner has done some great work. You can learn more about it in their other case study:

The Hard Work of Making Work Easier