“Let’s take a gemba walk.” This always sounds like a good idea to me but what my hosts had in mind in an organization I recently visited turned out to be something quite different from what I expected – and much better. They wanted me to participate in their daily management walk. But more specifically, they wanted me to observe their daily management process with an eye to how well they were doing the work of management.

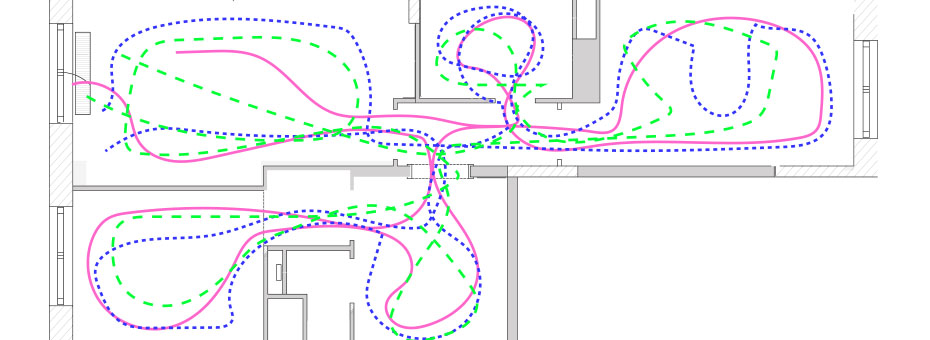

Early that morning we started with the front-line work: the actions that create value as perceived by customers. The work teams had already met at the start of their day and we followed the area leader who talked with each work team leader about the status of the work in relation to the normal run rate, and the problems needing immediate attention. The manager of the department where the teams worked then walked around to each of the area leaders to hear their summary of the situation and their plans for any needed countermeasures, before participating in a walk by all of the department heads (sales, operations, purchasing, engineering, finance, HR, etc.) This work of peering at boards, showing in green or red the status of practically every important activity underway in the business, proceeded through every department (easily possible within a few minutes in this medium-sized organization).

Were these latter laps around the business truly a management gemba walk? Absolutely. We started with the direct work of front-line value creators – which is where most folks think gemba walks occur &ndsah; and we then examined the incidental work of management at the multi-layered gemba of management. I believe it is hard to make progress in sustaining and improving performance without doing both. In the process of walking we observed all of the interactions across the departments. In the last round of our walk we observed two department heads making trade-offs in real time (with the agreement of the COO) to countermeasure a cross-departmental problem by asking what was best for the whole enterprise and not just their individual departments.

Interestingly, the CEO never said anything or “fixed” any problem. He was there to observe the management process so that later we could talk about how adequate this process was for a growing company.

This was certainly a lot of walking but for a good purpose: To confirm that the daily management system was working as it should and to think about making it better. However, as I walked, I pondered the fact that the simple term “gemba walk” that Dan Jones and I originally used to mean one thing has now been given several additional and sometimes confusing meanings. Let me explain.

We first used the term gemba walk (or value stream walk) in the early 1990s as a statement of revolutionary intent. (In lean speak, as a call to kaikaku, or revolution.) What we had in mind was to engage all managers touching a value stream in closely inspecting the progress of a product from the beginning of the value creation process to the end, crossing departments, companies, and even continents. This was done most famously for the can of cola Dan helped the UK grocer Tesco and its suppliers follow in Chapter 2 of Lean Thinking in 1996. We further elaborated our method in Dan’s and my workbook Seeing the Whole Value Stream in 2005, which followed the journey of a windshield wiper through four companies and two countries from start to finish. And I thought the term made a great title for my 2012 book Gemba Walks!

“So today I see a need for two types of gemba walks with different purposes: The value-stream walk to raise consciousness about the possibilities for dramatic end-to-end improvement (kaizen or kaikaku, as you will) and the management system walk to assess the ability of the management system to maintain stability, which is also the basis for successful improvement.” We wanted managers to routinely walk together to identify all of the steps involved in producing a product, all the time expended, and all of the information flows needed to control the process. At the end of the walk we wanted all of the managers touching the value stream to ask how they could create the same value with many fewer steps with much less cost in much less time with better quality while needing much less information. That would likely mean relocating many steps (both within facilities and between facilities) so the product would no longer need to be move between the value-creating steps. It would definitely mean creating a “value stream owner” to continually lead value stream walks to determine the current state, to describe a future state that could be reached soon, and to envision an ideal state that could be a north star for kaikaku (and kaizen too) going forward. A highly recommended means toward that end was the creation of a model line. (See my Lean Post Rethinking the Model Line.)

The 1990s were heady times as the full power of lean thinking was grasped for the first time by many managers outside the auto industry. But all revolutions devolve to evolution at some point and I have found myself in recent years using the term gemba walk mostly for shorter journeys inside the walls of one organization. I often lead these as my requirement for talking with managers about their lean transformation. My objective is consciousness raising to help managers see that the point kaizen they have settled for to date is merely the low-hanging fruit compared with the much bigger improvements that are possible through total process kaizen. An equally important objective is to help managers see the misfit between their current management system and the system needed to create and sustain high-performing value streams. (Again, see my previous Lean Post for details.)

So today I see a need for two types of gemba walks with different purposes: The value-stream walk to raise consciousness about the possibilities for dramatic end-to-end improvement (kaizen or kaikaku, as you will) and the management system walk to assess the ability of the management system to maintain stability, which is also the basis for successful improvement. They can be combined, of course, as I sometimes do, but that’s lot to take on at once.

However, more frequently I hear managers using the term gemba walk in a third way, often as a synonym for genchi gembutsu (which loosely means to go the place where value is created and see what the problems are.) In organizations where there is no effective daily management and no practical way for line mangers (rather than staffs) to tackle major improvements, I often hear senior leaders or their improvement team surrogates speak of “going to the gemba” to take a walk and “get to the bottom” of festering problems or barriers to improvements. Indeed, I have sometimes been asked to observe these activities.

And this type of walk is where the language gets interesting. Wikipedia, under the heading for “gemba walk”, reports that this is really the same as “management by walking around”, an idea popularized by Tom Peters in the 1980s (in the management best seller In Search of Excellence.) Peters’ injunction was for senior managers to cut through the “frozen middle” of management – whose members are allegedly busy obscuring the facts – in order to get to the front lines, see what is really going on, and sort it out.And today I routinely hear the term gemba walk being applied to any expedition by senior leaders outside of the conference room at the top of the organization to the gemba at the bottom to grasp the facts in pursuit of solving a problem.

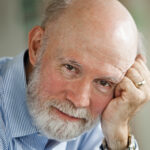

“But why is this third type of walk necessary for senior managers or Operational Excellence leaders if there is a robust daily management system in place to quickly identify and countermeasure daily problems and clear value stream leadership to think about improvement?” But why is this third type of walk necessary for senior managers or Operational Excellence leaders if there is a robust daily management system in place to quickly identify and countermeasure daily problems and clear value stream leadership to think about improvement? If front-line managers have established clear performance standards for their teams and intervene immediately when performance drifts from the standard and if the next levels of management are notified about conditions that cannot be brought back into the standard and immediately agree on corrective action (perhaps by going to the gemba with their direct reports) why do top-level managers and improvement staffs need to race to gemba too to fight fires? Are they simply walking around to look like leaders and get some exercise? Wouldn’t the organization be better served if they were spending their time thinking about ways to improve their management system or to kick-off the next big leap in performance – logically by taking a value stream or a management system walk – rather than worrying about specific problems no matter how troublesome in the short term?

A few weeks ago I observed what I believe is the best currently known way to operate a management system in a large organization. This was at the Toyota complex in Kentucky. At the 9 am meeting for department heads, where the current status of each department was shown on a board, the senior management team walked around the room from board to board, paying attention only to items marked in red. In each case the right manager at the right level had been to the gemba earlier in the morning to grasp the situation. He or she had collected a defective part or taken a picture or made a video for presentation to the group showing the problem and the proposed countermeasure. And the discussion was about the consequences of the countermeasure for other parts of the organization.

No mad race to the gemba by the CEO, no miles of walking by a dozen managers, no unnecessary transportation (muda), no management muri (overburden) at all. Instead the smooth working of a daily management system culminating with a short walk around a small room. The senior manager stood at one spot in the middle of the room – a green cross to emphasize safety – and then took it all in without walking at all. Something for the rest of us to think about as we develop our own alternatives to madly walking around.