This article, the first of two, describes the four critical characteristics of a help chain, or the 4S Help Chain Model. The second, to be published Thursday, April 29, explains how you can adapt the model to your product and process development work.

Whether our daily work is in a production line, technical center, medical facility, or other areas, when struggles and disruptions derail our efforts to provide value to customers, it’s critical to get back on track quickly. Implementing a simple yet concise quick response plan based on the 4S Help Chain Model will ensure you design the most effective approach to helping people when they encounter a problem and getting them back on track. Four essential characteristics make up this model, which works well in any situation — operations, product development, and other work areas.

Hands-On Help-Chain Learning at NUMMI

I learned the essential elements of the help chain while working at the General Motors / Toyota joint venture in California, called NUMMI. As many lean practitioners know, the New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc., is the first, unique location where Toyota installed lean principles into a U.S. vehicle assembly plant. During my time there, I realized that to get a truly lean system, there needed to be a strong connection between the social and technical systems, whether the work is done on the shop floor or in the technical center.

Though I initially went to NUMMI for a new product and process development activity, I was required to first work as a team member on the assembly line building small cars to gain hands-on experience with the Toyota Production System (TPS). The technical system was similar to what I experienced in previous assembly plants, and there were minor differences during the 80% of the time when the system was stable. One critical difference was the 20% of the time when the production system became unstable due to product mix, process variability, and other disruptions. The response to the instability is where the social system and the help chain differentiated itself at NUMMI.

A key learning at NUMMI was the recognition that quickly resolving common cause issues yields significant gains.

In my traditional assembly experience, variability and other disruptions would eventually cause sporadic line stoppages because there was no robust social system to provide timely and sufficient help to team members when they encountered issues or started falling behind. Many of these issues resulted from common cause variability, but the system was not designed to provide a mechanism for dealing with them before they impacted the overall line flow. In other words, common cause issues, such as parts becoming tangled and leading to extra sorting time, could end up stopping the line just like a special cause issue such as a conveyor belt breaking.

A key learning at NUMMI was the recognition that quickly resolving common cause issues yields significant gains. Individually, they might seem inconsequential, but they frequently occur throughout the day (and often in small duration), and they are difficult to predict. When taken in totality, common cause issues led to reduced quality, poor productivity, and low line efficiency (“death by a thousand cuts”).

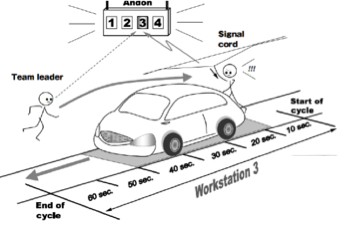

To support and develop the capability of the team members on the line to quickly address such problems, NUMMI leadership designed a social system to provide help (usually from the team leader) when a team member was falling behind. The goal was to help the team member resolve the issue, get production back to normal before the end of the work cycle, and enable the production system to keep flowing to meet customer expectations.

Source: Shook and Narusawa, Kaizen Express, LEI, 2009

The Critical Components of the 4S Help Chain Model

Most lean practitioners will recognize this approach as the andon system, but many misunderstand its role. The goal of an andon system isn’t to have operators stop the line to address a problem; the goal is to call for help to solve the problem and avoid a line stoppage.

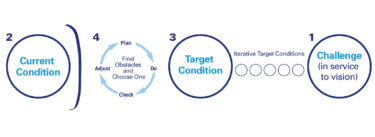

In hindsight, I’ve identified four essential characteristics of this social system at NUMMI that were missing in my previous operations and product and process development work. The detailed design of an actual, functioning help chain has more components and dimensions, but think of these four key characteristics as a 4S Help Chain Model, which can apply to operations, product development, and many other work areas:

- Sense

- Signal

- Swarm

- Solve

Sense is the ability to recognize normal from abnormal as quickly as possible. The first step in any problem-solving methodology is problem awareness and its relationship to the current performance. The responsibility is on the team member or value-adding person to sense a problem at the task level and understand the severity and type (common vs. special cause) of an abnormal condition. This capability requires that team members have an existing, reasonable standard or work plan that defines what is normal and expected; otherwise, they have no way to identify normal and abnormal.

At NUMMI, despite being a new team member, I knew within 20 seconds of my 60-second work cycle whether I was ahead or behind, as defined by the standard work, even though we were making a high mix of different content across vehicles. In the traditional vehicle assembly lines that I worked on before NUMMI, we didn’t know if there was an actual abnormal situation until the 60-second mark, leaving no time for getting back on track before the line stopped–and avoiding the ensuing glares from my co-workers.

Signal is communicating easily and rapidly to the appropriate person that you need help based on a determined set of conditions. At NUMMI, if I fell behind by a large amount of time that exceeded the limit, I would pull the andon cord. Then my team leader, who covered a zone of five stations, would be signaled via the low-cost yet effective visual and audible system to quickly provide me with the necessary support. My initial perception was that when I pulled the cord, the line would stop, but in reality, the line rarely stopped. Instead, it sent the signal that I needed help.

The team leader or other designated person would swarm my area to assess and diagnose the situation. The goal was to get my station back to standard before the end of the cycle, which we almost always achieved. Though this type of signaling occurred thousands of times each day across the entire NUMMI plant, the line efficiency and the plant productivity were at the top within the North American auto industry. This critical role of the team leader had clarity, and the company invested in developing team leaders’ ability to support team members.

To minimize the risk of having to stop the line, the team leader and team member quickly had to solve the pending abnormality — exceeding the manual work time, dealing with a component issue, struggling with a lingering equipment fault, and more — while also completing the remainder of the assembly work. They used two levels of problem-solving, depending on the issue:

- Level one (serve to protect) is to ensure safety and quality while keeping the line from physically stopping. At this level, the aim was to troubleshoot or complete a short-term problem-solving cycle of plan-do-check-act (PDCA), usually without identifying a root –cause. This type of problem-solving happened all day long with each common cause abnormality.

- 2. Level two (serve to prevent) is to understand the trends and major issues, get to the root cause, and work toward problem avoidance. This type of problem-solving usually happened offline or in weekly improvement circle meetings since it frequently required focus and collaboration.

Whether your work supports a manufacturing area or a technical center, the 4S characteristics (Sense, Signal, Swarm, Solve) of the help chain will ensure your work process continues with minimal interruptions. An effective PDCA problem-management cycle initially requires awareness, agreement, and alignment on the actual problem to be solved. It likewise needs people with the capability and means to enact proper countermeasures to the critical struggles and difficulties that we face every day.

Subscribe to The Design Brief to get the latest insights in Lean Product and Process Development.