Everyone who has caught the lean bug shares at least one symptom: We love to observe work. We love to go to the gemba and watch the value-creating work, the real work of the business. But when leaders “go to the gemba,” they go for a reason: To help discover how to improve the work processes. Still, I’m often asked: “What do you look for…?” So here are some guidelines I use when doing a gemba walk as an outside advisor.

Go See, Ask Why, Show Respect

The words of Toyota Chairman Fujio Cho, “Go see, ask why, show respect,” are now famous as basic lean principles. I first heard Mr. Cho speak those words when I was deputy general manager during the early 1990s start-up of the Toyota Supplier Support Center in the U.S. Each week began with a meeting with Mr. Cho, who was my advisor, to discuss activities, progress, problems, and plans.

Go see, ask why, show respect is the way we turn the philosophy of scientific empiricism into actual behavior. We go observe what is really happening (at the gemba where the work takes place) while showing respect to the people involved, especially those who do the real value-creating work of the business. So now let’s do a job breakdown.

Go See

It starts with “go see,” so how do you go see? What do you look for?

We want to understand every gemba from the standpoints of Purpose, Process, and People. Asked most simply and directly: Is management working to align people and processes to achieve a purpose? Are processes designed to enable people to work toward achieving organizational purpose? Here are some questions to dig deeper into this:

- What is the purpose of this gemba and the broader organization? Are they aligned? Can you see that alignment in the process and the people?

- Are processes designed consistently to achieve the purpose?

- Are people engaged in working to achieve the purpose, and are they supported in this work by the processes?

Although purpose ostensibly comes first, I usually focus on process when walking a gemba. Still, I often begin by asking just a few simple, direct questions about purpose. What is the organization or individual trying to accomplish — objectives and problems — in general and/or today? After this, we begin our walk, observing and asking questions that focus on the process. Later, I always circle back to ask more in-depth questions about purpose, objectives, and problems.

Observing the process and people dimensions means seeking to understand the gemba (whether the specific work site you’re visiting or the broader organization) as a socio-technical system. I like to try to understand the technical side first, though I observe both dimensions in parallel. If I can understand what this gemba is trying to accomplish technically, then I can easily conceive the best questions to ask to help them better understand where their real problems are and what they need to do next.

Based on the current situation of your gemba, I can begin to consider exactly what this gemba and these people need to learn. Then, I can think of how I can help them learn it.

Ask Why

Having gone to see, now standing at the gemba, how do we go about understanding or analyzing the technical or process side of understanding the gemba-as-system? First, a thought question for you:

What did you look for last time you went to the gemba? What do you look for whenever you go to the gemba?

Here are four ways people view work through very different “lean lenses”:

- Solution view

- Look for opportunities to use lean tools

- You must be careful here. Using a tool for the tool’s sake is one of the most common reasons for failure of lean initiatives large or small, and, once the pattern has been set, is most difficult to overcome.

- Remember that lean thinking is about never jumping to conclusions or solutions, so the solution view isn’t really a lean view at all. Still, it is a very common among well-intentioned and even highly experienced practitioners.

- Look for opportunities to use lean tools

- Waste view

- Look for waste

- The seven (or eight) types

- Especially overproduction

- Other types

- Look for waste

- Problem view

- Start with the worksite objectives

- Confirm: “What are you trying to achieve?

- Ask: “Why can’t you?”

- Focus on system, quality, delivery, cost, morale

- Problems: the presenting symptom or problem in performance

- Causes: points of cause in the work

- Start with the worksite objectives

- Kaizen view – seek patterns, forms, tools, routines, “kata”

- Apply at the system level — “system kaizen”

- Value-stream mapping plus material and information flow for system design

- Apply at the point level — “point kaizen”

- Standardized work and daily kaizen

- Apply at the system level — “system kaizen”

The kaizen and problem views are solidly founded on the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) process. The problem view is flexible and requires no specific lean knowledge, but it can take a long time to see results, and the path may be very uncertain. As the name implies, it is enabled by a robust problem-solving process that can take many specific forms. Toyota’s eight-step (Toyota Business Process – TBP) process is a very good one. Seek it out and give it a try.

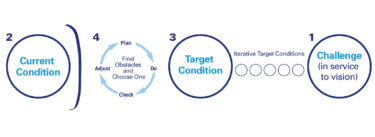

Like the problem view, the kaizen view embodies PDCA, but it also looks to establish specific (whether new or well-understood) patterns of behaviors. These patterns — kata — lead to learning, continuous improvement, and innovation of new patterns. The concept is to “enter through form” — to master the behavior patterns and make them habitual to learn and change your thinking. Take a look at Mike Rother’s book, Toyota Kata (2009).

The patterns, routines, and tools of the Toyota Production System are designed to be structures for improvement and learning.

When observing with a kaizen view, a good approach is to start your gemba walk as close as possible to the customer and work your way back, considering “what would flow look like?” Think about the system as well as the individual processes. The patterns, routines, and tools of the Toyota Production System are designed to be structures for improvement and learning. They help us see clearly and understand and also help us teach and mentor. So, they are just the things (solutions and means of deriving solutions) we teach, the vehicles through which we can ask questions to teach and mentor.

Unfortunately, the kaizen view is sorely missing in most gemba walks I observe. And yet I am pleased that more Lean Thinkers are moving beyond the “solutions lens” (again, which is not lean thinking at all), past the simple waste lens (yes, we don’t want waste, but we need to seek understanding of why the waste is there and what we can do about the causes of the waste), and many are working firmly within a problem-solving framework. This shift represents significant progress for the lean community.

Asking Questions at the Gemba

Although it is the second element of “go see, ask why, show respect,” “why?” is not the first question we want to ask at the gemba. First, ask what, then why, then what if, and finally, why not.

The purpose and process of asking why after you have observed the gemba: Your car has a GPS; you need a GTS — a “grasp the situation” — process. We must train our lean eyes to see and minds to ask what first. Asking why — to diagnose — comes later. As David Verble says, “Ask no ‘why?’ before its time.”

Show Respect

When going to see, lean thinking mandates (yes, mandates) that we show respect to all the people, especially those who do the value-creating work of the business, the activities that create value for customers. So, when visiting any gemba, through showing respect for the workers, we also show respect for customers and the company, analyzing for evidence of disconnects between stated objectives, perhaps expressed in the organization’s “true north” visions statements, versus what we observed at the gemba.

Always look for signs of disrespect toward:

- Workers — especially muri or overburden

- Customers — poor delivery or poor quality – especially from controllable mura or fluctuation and variation

- The enterprise itself — found in problems and muda or waste, in all its forms

But, the worker is the first and best place to look. Think of this flow:

Respect People → Rely on People → Develop People → Challenge People

We respect people because it’s the right thing to do and makes good business sense.

Think of building your operating system from the value-creating worker out. Observe the worker and steadily take away every bit of nonvalue-creating “work.” Continue doing that, engaging the worker in the process until nothing is left except value-creating work, until all the waste has been eliminated and nonvalue-creating work isolated and taken away, distributed to support operations.

To achieve that level of “leanness,” you will find that you must engage the hearts and minds of the people doing the work. You will have to rely on them, just as you have to rely on them to come to work and do their job so you can get paid by your customers.

Once we’ve recognized that we have no choice but to rely on our employees, it is easy to see the next step, developing them. Because as the lean saying goes, “Before we make product, we make people.”

Which leads directly to the most characteristically lean dimension of respect for people: challenge. Respect for people is often mistaken for establishing the enlightened modern democratic workplace in which everyone is treated with great deference and politically correct politeness. Yet, respect demands that we challenge each other to be the best we can be. Setting challenging expectations is one of the most critical skills of lean leadership.

Most of all, respect means doing what we can to make things better for workers, which starts by not making things worse. And we still find leaders doing more of their share of damage even as they try to help! That’s why the first rule of gemba walking is: “Do no harm!”

A Note on Gemba-Based Leadership

Everywhere we go, we still find overwhelming evidence that the conventional view of a leader is as an answer man (or woman), that the leader always should have a ready answer, and that the leader’s answer is always correct — remains strong. And indeed, the leader’s role in providing the vision, setting the direction, and showing the path to true north is foundational to lean success.

Unfortunately, we also see overwhelming evidence of the damage done by the broadcast of executive answers that reverberate negatively throughout the organization.

These guidelines are my own, based on doing gemba visits as an invited outside observer. Each of us needs to consider first, depending on where you work in your organization, where is your real gemba? It’s easy for leaders to cause more trouble than they alleviate. CEOs who try to directly eliminate waste at the gemba often generate more waste than they prevent!

Here are two simple sets of questions for you:

We already asked: “What did you look for the last time you went to the gemba?” “What do you look for (generally) when you go to the gemba?”

Then ask, “What did you do?”

After that, the next set of questions is:

- “What will you look for next time you go to the gemba?”

- “What will you look for (generally) when you go to the gemba?”

- “What will you do?”

In other words, ask: What will you do to help?

Whenever leaders issue prescriptions from afar, bad things are likely to happen.

Whenever leaders issue prescriptions from afar, bad things are likely to happen. The best antidote we know? Confirm what is happening as it is happening. Diagnose and prescribe as close in time and place as possible to the work, preferably in partnership with the person or people doing the work. That is one of lean management’s most vital principles and practices.

Editor’s Note: This Lean Post is an updated version of an article published on June 21, 2011.

Work Observation Practice

Learn to observe and understand work processes at the level of detail required to improve them.

The concept and approach is a different way to learn how to accomplish our personal goals.

Great insight and read

Meaningful interactiion over Observing the worker everytime

I saw this Observe the worker in your article one time and for me this is crucial in my current setting in teaching

Observing the worker feels like going to the zoo and watching the animals.