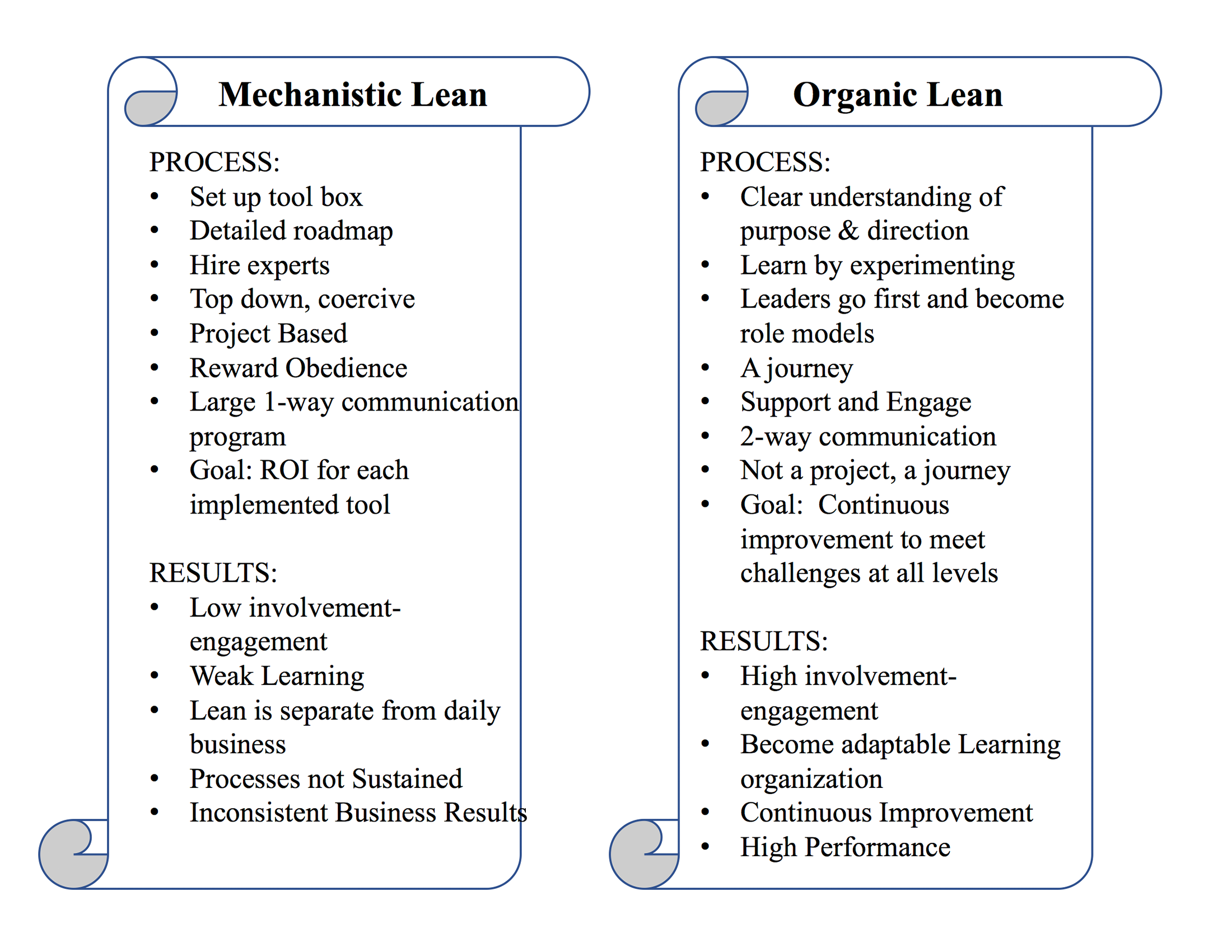

Given all the distinctions among mechanistic organization, organic organization, and innovative combinations in enabling bureaucracy, how do most organizations deploy lean systems? I teach a three-day master class on lean leadership and pose this question to my “students,” who are mostly executives. With only a broad definition of the distinction between organic and mechanistic deployment of lean, I ask them to call out characteristics of each. They typically do so enthusiastically.

These categories delineate a clear difference between the mechanistic approach—project based, expert driven, top down, tool–and the organic approach—purpose driven, a journey, engaging people, coaching.

My students believe the mechanistic approach is faster and more efficient, but the organic approach is more robust and sustainable.

When I ask the students which they prefer, and believe is the most effective, they overwhelmingly vote for the organic approach. They usually say the mechanistic approach is faster and more efficient, but the organic approach is more robust and sustainable. Someone will inevitably point out that maybe it is not either/or, but there may be a role for both. I then describe enabling bureaucracy, and the light bulbs go on. Heads nod, and they all agree what is what they are aiming for.

Most report that they are using a mechanistic approach and wonder if they should abandon that and move toward an organic approach. I answer that there may be some sense in starting with a broad mechanistic deployment led by lean specialists, and then build on that base more organic approaches.

The mechanistic approach often leads to measurable results and captures the interest of senior executives. There is an ROI. And the mechanistic approach can begin to establish a flow in the process and educate people about basic lean concepts. But if the rollout of lean is limited only to mechanistic deployment, the new systems are likely to devolved toward the original mass production systems when the lean specialists move on to other projects.

In contrast, Toyota prefers to start organically with the model line process—learn deeply by starting with developing the system in one place—which takes most time and does not provide the quick results across the enterprise that many senior executives impatiently expect. On the other hand, the model line approach leads to deep learning and ownership by the managers and workforce, which is crucial to building sustainability and continuous improvement in the new systems.

(This article is adapted from the new Second Edition of The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer.)

Executing Strategy

Connecting Hoshin to Daily Management and A3.

I can give real examples from my country, Jordan. The trend here is purely the mechanistic approach. There are a few lean consulting companies who provide lean consulting on project basis. Every project spans three to four months. The outcomes are some improvements that show impressive results but are no way sustainable.

There is a minimal engagement of the operators and it is a top-down work based on the lean tools. The consultants convince the company management to implement a set of tools to improve certain areas. The consultants, mainly, do the work and leave. The company is not able to proceed with more improvements.

What adds insult to injury, is that the official industrial authorities promote such short-term lean projects and they even fund them.

I believe the problem is that everyone is looking for “quick wins”. This is lean Myopia. No one has the interest to invest in people and time to cultivate a culture of continuous improvement based on engagement, “learning by doing” and problem solving.

The consultant makes quick money, the company management scores points and possibly finds it a way to impress their Boards, and the authorities count projects.