Several hundred managers and continuous improvement professionals attended the Lean Enterprise Institute webinar “Beyond Problem-Solving: Other Facets of the A3 Process You Should Know and Practice” — and sent in scores of questions. They were more than presenter David Verble could answer in an hour, so he’s tackling them in follow-up articles on the Lean Post. The latest one follows. (Make sure you are subscribed to the Lean Post to get alerts when we post new answers.)

Q: What do you do if while working on an A3 for a complex process, you find multiple issues and root causes?

David: Most processes are complex in some way. They have different people doing different work to create a common output for a customer. There are relationships and handoffs and interdependencies in the process. There are managers, stakeholders, suppliers, internal customers at the next process, and end customers who have different perspectives on how the process should operate and different opinions about improving it.Only now should you shift to the technical side of problem-solving by rigorously breaking down the problem where it happens into smaller problems, factors, and conditions that are contributing to its impact on workflow performance as a whole.

So, a good practice is to avoid the temptation to quickly define a problem — or what you think is a problem — in vague terms or from a high level, e.g., purchasing is not cooperating or housekeeping is too slow turning around rooms. Do this by beginning your problem-solving thinking on what I call the social side. When you first recognize a condition or event that you believe should not be happening, ask yourself:

- Is it within my scope and influence to address this problem by myself?

- Is the problem having a sufficient impact on process performance, customer(s), or the business that it clearly needs to be addressed?

- Do work standards show or do other people agree that what I think should not be happening actually should not be happening?

- Do I have or can I get evidence to convince others who must agree that “we” need to address the problem?

Even if you answer yes to all these questions, you aren’t ready to think about solutions. Instead, step back and get some perspective on the situation by taking three actions:

- Go to where the problem occurs to watch the work being done. Talk to people doing the work and those who support the process. Find out what they see and experience. Ask what slows down their work, what frustrates them as they try to work as planned, what do they know about the problem, and what do they think would make their work go better. But don’t ask directly if they see problems in the process. It frequently happens that we work around and through problems so often that we don’t recognize them as problems.

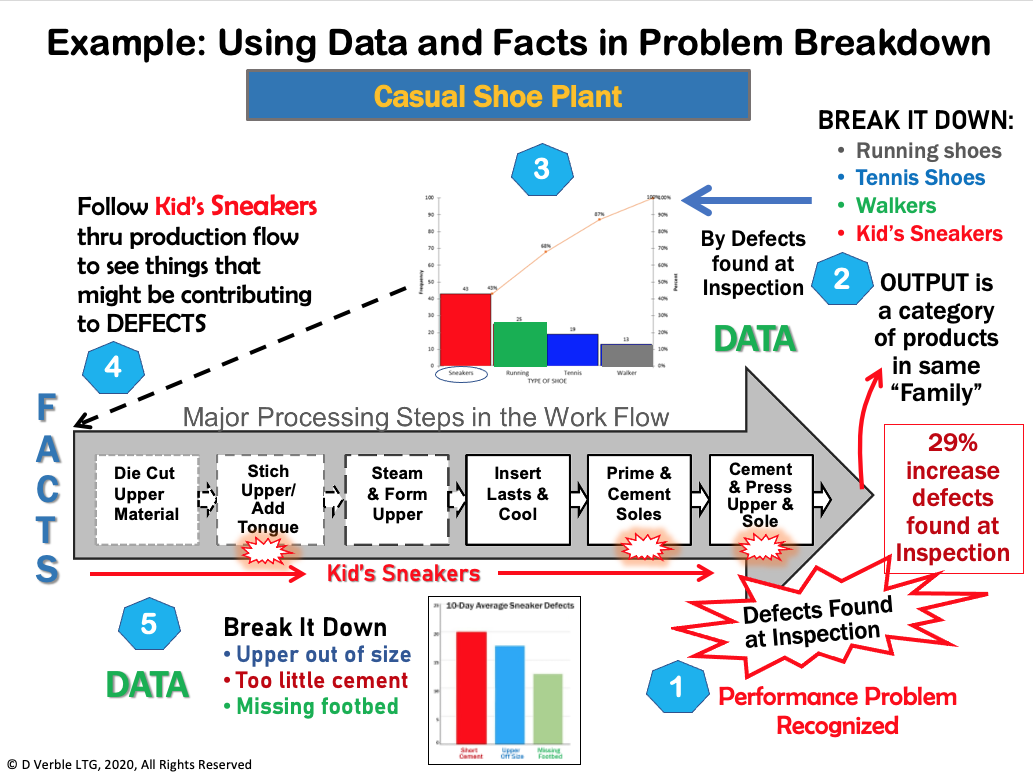

- Now use what you have learned to broaden your perspective and put the problem in context. Draw a simple map of the process flow, using no more than five or six high-level value-adding steps. You can do a deep dive and create a complete value-stream map later if it’s needed to understand the process in detail. Include process outputs on the map, what value they provide, how performance is measured and tracked, and where the process starts and ends. Refine your understanding by walking the process to show the map to people involved in each processing step. Observe how value is created at each step and how performance is affected by what happens or doesn’t happen at each step.

- Complete your high-level perspective of the workflow by observing what is happening or not happening at the point where the problem occurs. Note how it affects the end customer of the process. You want to see your concern about the problem in a larger context by “anchoring” it to its impact on the end customer and others working downstream. The importance and urgency of tackling the problem are not just based on the fact that it is occurring but on its impact from the perspective of the process as a whole. What performance measures show that impact?

Now you are ready to address the problem in context, not as an isolated event. Only now should you shift to the technical side of problem-solving by rigorously breaking down the problem where it happens into smaller problems, factors, and conditions that are contributing to its impact on workflow performance as a whole. (See the graphic below for an illustration of the overall process.)

Mind the Gap

Breaking down your problem situation is a two-, possibly three-step process.

First, consider the nature of the unwanted condition or occurrence at its location in the process as the starting point to look to the end of the process to see if your problem is related to a performance gap in delivery to the customer and/or the business. Gaps can include customer returns of defective products, complaints about incorrect charges, the business cost of assembly, etc. Identify the smaller problems in the process at the point where they occur to see if any fall into the same general category as the performance gap (defective parts, complaints, etc.).

Next, sort the incidents of related smaller problems you found into sub-categories. For example, defective parts may fall into sub-categories of wrong sizes, damaged, off-color, rough surface, wrong account number, etc. Determine the number of occurrences of each sub-category.

This is where an additional step may be needed. If data for the number and type of occurrences does not exist, establish a method of collecting it such as a check-sheet or tracking sheet to capture a record of the occurrences. It is important to get input from people doing the work to determine the sub-categories to track. Engaging them now to create the tracking process should make it easier to gain their agreement to take on the extra work of doing the collection. When you have the raw data, it will need to be counted and organized in a table, so the size of each category is immediately apparent.

Then Mind the Smaller Gaps

Finally, use the table to select the sub-categories that need attention first based on size and their direct impact on the performance gap in delivery to the customer. It is often helpful to use the data to create a Pareto diagram showing the size of each sub-category in comparison to the total number of incidences in the overall category. Obviously, the size of a sub-category is of primary importance in deciding which of the smaller problems you have discovered are contributing to the performance gap to tackle first.

Remember that impact on the gap in performance in delivery to the customer and business is also a major consideration in prioritizing contributing problems to focus on. Look for contributing problems that are directly linked to the performance gap. For example, customer returns of defective products is a broad category that may include several products. So, make sure the sub-categories of contributing problems to returned defective parts are directly linked to products from the location of your problem in the overall process.

That means when prioritizing the contributing problems to focus on, you may need to sort the defective products counted in the overall performance gap to confirm those contributing problems directly related to the defective products your process is responsible for producing. This will give you line-of-sight to the number of returns from the process you need to reduce and gives a way to judge the effectiveness of your problem-solving effort.

What Steps to Take Next:

- Read David’s reply to an earlier question about problem-solving methods. Dueling Methods: 8D and A3.

Managing to Learn

An Introduction to A3 Leadership and Problem-Solving.