Most lean transformation is grounded in the daily work at the front lines—the gemba—where tangible methods like one-piece flow connect detailed elements of work to broader principles of continuous improvement. Individual projects can boost quality, cut costs, reduce inventory and more. Unfortunately, these changes rarely generate large enough numbers to register as more than a blip on the radar of senior executives. While proven lean practices such as kanban, and visual management, and daily management routines, can produce profound results, senior-level planning and decision-making often chugs along in parallel yet separate tracks.

Hoshin kanri, or policy deployment, connects long-term strategy and business plans to operational objectives, and cascades down to shopfloor targets.

One way to get senior management on board is to get them involved. Gemba walks, or even more immersive participation in kaizen events, can excite senior management and engage them with the complex realities of the value-added work. I personally have yet to see a senior executive not get excited about being at the gemba and getting their hands dirty. Still, the potential gains from these types of involvement are all too often erased when executives go back to their calls, meetings and computers, and get enmeshed in tactical planning, making deals, and reporting out to shareholders.

Hoshin kanri provides an opportunity to change that.

Hoshin kanri, aka policy deployment, connects long-term strategy and business plans to operational objectives, and cascades down to shopfloor targets. HK aligns direction so the middle and bottom are working toward objectives that matter to the top, and so all those great improvement activities are focused on achieving the big results executives will notice. It also provides a reason for the people who are passionate about lean transformation to have a meaningful dialogue with the C-suite.

In an earlier Lean Post I wrote about the difference between mechanistic and organic approaches to lean. All too often hoshin kanri is considered just another tool in the tool kit and introduced mechanistically. Ask any senior executive if they would like a way to achieve their goals better and it is hard to imagine why they would say no. Explain there is a tool called hoshin kanri that will let them more clearly communicate what they want and expect and get their management team aligned to meet their goals. Why not? They will probably ask what you need from them.

If this means filling out a tool like an X-Matrix to clarify the strategic direction and how this relates to KPIs, projects, and individual leader responsibilities that would sound fine. Go for it! What is likely to happen is meetings are held to set targets that are aligned across levels and everyone will be encouraged to meet their objectives, but otherwise nothing will change. After all, the company has been managing by objectives for decades.

At Toyota hoshin kanri is part of an organic system of management. It was first introduced in the 1960s to increase quality to world class levels and work toward the concrete goal of winning the prestigious Deming Award. It has become an annual planning and execution process throughout the company ever since. It is institutionalized into the culture and goes far beyond some meetings to agree on targets.

Making the Argument for Hoshin Kanri

Consider a lean change agent who has experience with true hoshin kanri, similar to what is practiced organically in Toyota, attempting to get the CEO on board. Let’s imagine how that person could approach a conversation with a relatively open-minded CEO about this.

Lean Change Agent, or LCA (a bit nervous): We have gotten some great results from our lean six sigma program, but the projects seem scattered and not always related to the company strategy and goals. I think we can do better. You might have heard of hoshin kanri, originally part of Japanese total quality management, that connects our goals to our improvement activities, providing a clear direction.

Big Boss, or BB: Sounds interesting. What does it involve?

LCA: It is an annual planning and execution process that supports a multiyear strategy and business plan. It is actually a pretty serious commitment by you and the whole management team and would involve a process of goal setting and planning and then collaboration throughout the year. Think of it as a process of working together toward a vision and a strategy. The starting point is reviewing the company strategy and business plans and then developing one-year challenging goals to move us in that direction.

BB (intrigued): You haven’t scared me away yet. Please say more.

LCA: You share these top-level goals with your VPs and ask them to work on their measurable challenges to support the top-level goals. You also ask for a high-level plan for what themes they would focus on to work toward the challenges.

BB (a little impatient): You must know that we already have business objectives at the top level—and that the VPs all meet with the C-suite to set objectives for their units. And I hold them accountable with regular report-outs. So…what is different about this “hoshin kanri?”

LCA (backtracking): Good question, thank you. I agree that we do a good job defining the business outcomes we want. The emphasis here is on planning that goes beyond that. The VPs will need to put in time to develop a plan. We currently use A3 reports for problem-solving in our lean program. That is also a good tool for making proposals with a good deal of back-and-forth dialogue.

In these VP proposals we would ask them to look at the current condition in relation to the business objectives and identify the biggest opportunities for improvement: whether the focus is on cost, quality, lead time, safety, product innovation, or even human resource development. The business outcomes tell us what we want the results to be, and the focus areas provide process measures. We can identify the levers to focus on in order to achieve the outcomes. This gets us all further into operations and how we do things.

BB: Okay. I can see how that level of planning would add to the workload…and go deeper than usual for us.

LCA: Yes. And we would go even further by asking the VPs to repeat the same process with their managers. They would help each manager clarify the desired outcomes, and then ask the manager to work on a plan to identify where to focus and identify process metrics and targets.

In this context, the A3 process done right is more than simply writing a report: it is a collaborative planning process between a boss and their subordinates. When it is done well the boss behaves like a coach, who is asking challenging questions and often sending people back to understand the current condition better and to consider benchmarks, and to work and rework the plan. This cascades down to all levels of managers and supervisors.

BB: Couldn’t this be, well, time-consuming? How long does this take?

LCA: Good question, thank you. This is not the same for every company; and honestly, I would expect it to take longer the first year we try it. But it can be a truly transformative practice for the company. Toyota has made HK a routine annual planning process going back to the 1960s when its focus was on improving the quality of its vehicles. It takes them three months of planning—the last quarter of the year planning for the next year.

BB: Hmmm. I can see why this would take a serious commitment from me and the whole management team.

LCA: Not to scare you off, but this is just the planning phase. Execution is a whole other process.

BB (looks at watch): OK, I’ll bite. What is that about?

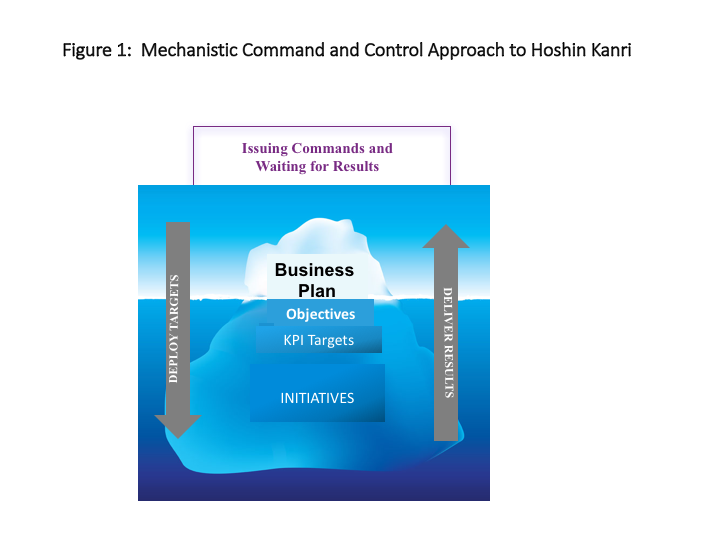

LCA: These diagrams might help. I believe our current way of business planning and goal setting looks something like an iceberg (figure 1). I have been impressed by our approach to defining strategy—not many firms are good at this. I also think the five-year and three-year business plans make a lot of sense… though these are mostly financial plans.

And here’s the rub. Once the action starts—and no offense boss but you are very busy with many things outside the company and delegate execution to our VPs who tend to then delegate objectives to middle management—but as soon as we shift to implementation, all this work becomes a “management exception system.” The only things that get C-suite attention are the big problems that bubble up to the surface. The beauty of this approach is that as long as things are going well, you can review the metrics on your computer without getting too involved below the water level.

BB (a little offended): Well, I think this is quite a simplification, but I will play along. Go on.

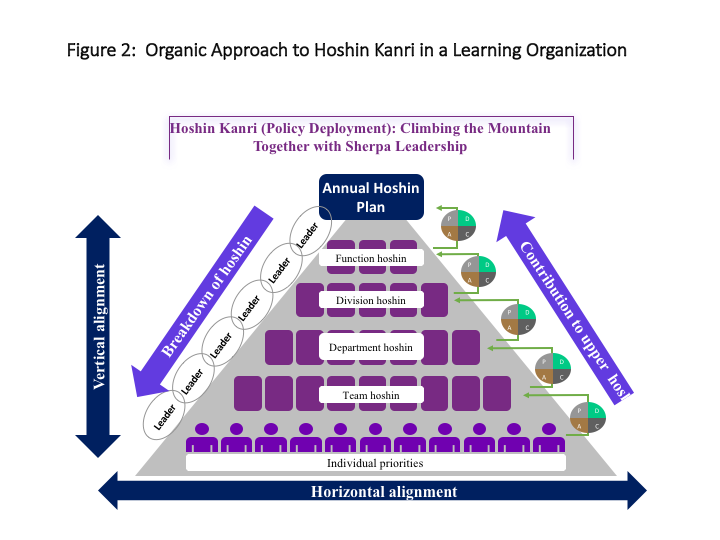

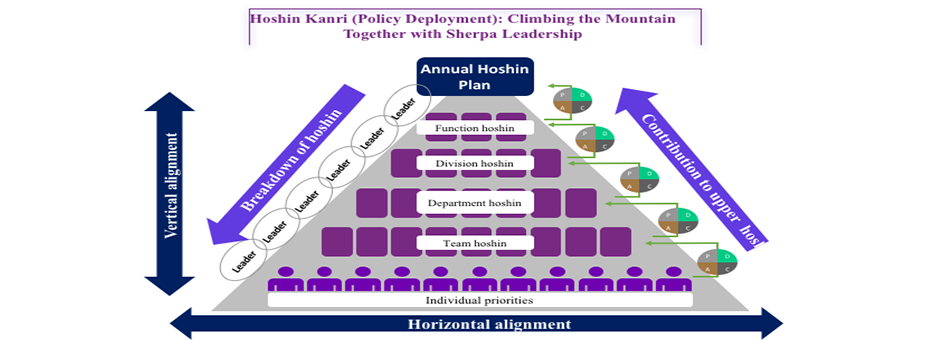

LCA: Yes, absolutely an oversimplification. My main point is that the contrast with what a company like Toyota does is pretty stark. Instead of an iceberg, think of our business like a mountain that we are climbing (see figure 2). I know you have taken on some pretty big mountain climbs, so you know more about this than I do. But my understanding is that it is critical to plan for the mountain climb, anticipate as much as possible the adverse conditions you might face, get all the right gear, train as a group and then reality hits on the first step. There are many quotes about this–like Mike Tyson who said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” Reality packs a mean wallop.

BB (smiling): Okay now you are getting my attention.

LCA (encouraged): Great! Now boss, with your experience and the other experienced leaders of the group, if you were to go off ahead up the mountain and say “good luck, we will meet at the top” people are likely to die.

Hoshin kanri at Toyota is more like mountain climbing, where the leaders come down from the mountain and act like Sherpas: coaching, motivating, and guiding, while letting people struggle within guard rails. Execution is a very dynamic, interactive process. In hoshin kanri there is a phase called “catchball” where boss and subordinate throw a ball back and forth negotiating over targets. At Toyota, catchball is happening every day and formal reviews have few surprises because the bosses are there every day at the gemba with the people.

BB (reflective): Hmmm, this is quite different from our current leadership style. It seems like the changes go far beyond a tool and get to the core of our culture. I like the mountain climbing analogy. I can relate to that…execution as mountain climbing, overcoming obstacles uncovered along the way. I need to think more about this. Why don’t we adjourn for now? Could you create a proposal on how we might get started with this?

LCA (beaming): On it, boss!

Understand HK as a Living Process of Planning, Testing Ideas, Adapting, and Learning

Hoshin kanri is frequently misunderstood as a specific tool for a specific phase of planning. Most of the companies that tell me they are doing HK are actually doing management by objectives in disguise. They focus on desired outcomes, usually financial, getting people to sign up, and then delegating. Anything more is perceived as micro-management. Empower people, and then hold them accountable, and a bad result can mean the end of the line for that leader.

Pursuing hoshin kanri is a never-ending process of learning and getting better.

At Toyota, leaders are developed by bosses who act as teachers and coaches. Hoshin kanri is a natural part of organizational life and is a powerful tool for people development. I suspect that the environmental disasters that regularly hit the islands of Japan help influence people to see the world as complex and unpredictable. Planning is more rigorous than in most companies: it includes understanding the current state, identifying potential obstacles, and developing process metrics that are more directly controllable than outcomes. But the plan is viewed as just that—a plan. It provides only broad guidelines as people then need to adapt every day to reality, with daily meetings to assess progress and take corrective action at all levels.

Hoshin kanri is a living process of planning, testing ideas, adapting, and learning. Improvement activities, like what we call “lean,” now have a clear direction. Rather than broadly applying tools, members work towards clear targets addressing the next big obstacle. This approach reflects focused “scientific thinking” instead of scattered implementation.

True practice of HK and its underlying goals is a challenging goal. Getting there involves far more than introducing a tool like the X-matrix and filling it in after catch ball meetings. Pursuing HK is a never-ending process of learning and getting better.

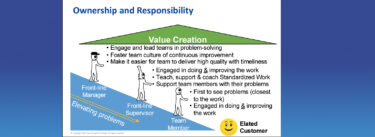

In many cases it may be premature to introduce hoshin kanri before the organization has some experience with developing lean processes and learning a scientific approach to problem-solving and achieving goals. At Toyota they teach that there are two key disciplines necessary to make hoshin kanri work—problem-solving skills and on-the-job development (coaching). For less mature organizations, it can make sense to start at the top 2 levels and develop some skill before deploying HK to every level. The power of aligning goals and narrowing the focus of our improvement can be game changing. This enduring power comes from evolving into a learning organization with true collaboration across departments and levels.

Hoshin Kanri

Aligning and Executing on Your Organizational Objectives.

There are various approaches to successful strategy planning and execution. That’s a big challenge to undertake, but when done correctly, the benefits are immense.

Regardless of what stage of your Hoshin Kanri (Japanese term) lean journey you’re at, this approach is exactly what your organisation and leadership team needs, to embrace daily improvement, maintain the gains, and achieve your breakthroughs.