As a leader, do you aspire to have “everybody, everyday” making things better? (Shoutout to GBMP!) Are you struggling to realize that within your organization? If the leaders I’m talking to are representative, then the answer is yes. For them, given the enormous volume of problems to solve, it’s an existential need. So, they are trying to develop lean management systems that facilitate and enable problem-solving by the “right people.”

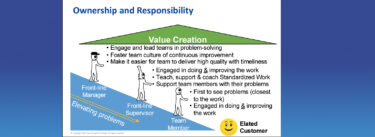

Two questions that a leader trying such an enabling system should ask are, “What are the key success factors for developing such a system? And what, specifically, is needed from me?” But a word of caution: answering these questions is not simply an intellectual pursuit. Instead, leaders should engage with their organization’s frontline work (and workers!). Only then can leaders fully appreciate and become aware of what’s required to tackle the work’s problems effectively.

… leaders should engage with their organization’s frontline work (and workers!). Only then can leaders fully appreciate and become aware of what’s required to tackle the work’s problems effectively.

These thoughts remind me of a corporate executive’s frustrating first visit to a model store where I was working as a coach. Because he was one of the experiment’s sponsors, the stakes of his visit were high. Executives at the retail food company had been exploring lean as a way to respond to increasingly aggressive competition and stubbornly tight margins. They hoped that frontline-generated improvements would help turn around overall performance.

Past efforts at “continuous improvement” had been the responsibility of a corporate staff that collected and disseminated “best practices.” But several executives had become worried that the rate of improvement was too slow. Some even worried that the promise of “best practices” was false advertising, questioning if improvements were happening at all. The new way – lean management – would seek to enlist folks working in stores to take responsibility for improvement too. If effective, executives hypothesized, the rate of improvement would grow exponentially.

We (a handful of frontline associates, their team leader, the store manager, a small support staff, and I) were excited about the executive’s visit. We had been reporting out to him for a while, telling him about the things we were trying, the progress we were making, and the momentum we felt like we were building. And we wanted to keep going! But the gemba must speak for itself. He had to see firsthand.

For example, we had told him about the changes we had made to improve the shopping experience. Problematically, customers often had to wait for popular made-to-order products to be prepared. In fact, in another store, this problem was so bad that a DMV-inspired take-a-number system had been established. (Have you ever thought of the DMV as a benchmark?) That store had also installed a park bench. (No, I’m not kidding.) The message to customers was clear: “Take a number. Have a seat. It’s going to be a while.”

To address the problem of customers waiting, the team had boosted flow to reduce lead time.

To address the problem of customers waiting, the team had boosted flow to reduce lead time. They had rearranged products in the display case, making the most popular products easier for customers to see and for workers to reach. Workstations were also repositioned to reduce unnecessary motions when doing the work. The team had also redistributed work elements amongst themselves. Elements for the “online” work to meet immediate customer needs (e.g., taking an order, assembling the product) were assigned to most team members. While elements for the “offline” work for future customer needs (e.g., replenishing, cleaning) were assigned to one team member. By redistributing the work elements in this way, workers were prevented from walking away from customers and their orders mid-process. Added up, these changes were dramatically reducing wait times.

By tackling this problem, the team was learning practical process kaizen skills such as work observation, breakdown of the elements, analysis of the causal factors that led to wasteful motion, and practical improvement skills for ongoing, daily experimentation. They were proving, to themselves at least, that they could handle that responsibility capably. However, we were upsetting the apple cart (pun intended!). And we were discovering how the upper management and surrounding systems could get in the way. (It’s worth noting that such a discovery is part of the value of a model line experiment.)

To illustrate this conflict, we looked at how the team had rearranged products in the display case. They did this to place their store’s highest-selling items in the most convenient location from their customers’ and the workers’ perspectives. As a result, shopping was made easier, as was the work. However, the layout changes were unusual, putting the store out of compliance with the company’s generic merchandising standards. Consequently, the folks who owned the merchandising standards were making a fuss.

Why would such a critical standard be governed — then imposed on every store — by folks outside of the stores? Why not place ownership with store teams …?

Why would such a critical standard be governed — then imposed on every store — by folks outside of the stores? Why not place ownership with store teams who are (a) closest to the customer, (b) impacted by the layout as far as their work goes, and (c) showing themselves to be more than capable of managing the basic needs of customers and workers? These were questions we wanted to discuss with the visiting executive.

But before we could have a productive discussion, we believed he needed to understand the team’s thinking and the process they had gone through that led to the visible changes. Why did we think this was necessary? For three reasons: (1) to demonstrate that their thinking was sound, (2) to build his trust in their capability to handle responsibility for process kaizen, and (3) to show him there was a practical way to build problem-solving capability in store teams.

This final point was crucial. Ultimately, the company wanted to spread improvement ideas from this store to hundreds of other stores. And the thesis of the new approach for the company was “to spread improvement,” which meant building capability for improvement in systems, processes, and most importantly, people. Specifically, to build capability of the people who do the value-creating work for customers.

I will never forget how that executive’s first visit played out. When he arrived, we quickly ushered him to the gemba. Our strategy for the visit was “show, don’t tell.” While we did not know the executive all that well, we did recognize that he did not like to be “handled.” Understandably, exhibiting his independence in thought and action was important to him. Although we underestimated the degree to which that was true.

Upon entering the gemba, he scanned the environment and commented on the work area’s orderliness and cleanliness. Then, he checked out the visuals on the wall with KPIs and information about various problem-solving activities. He seemed to approve of what he saw. Then, he turned to the frontline associates and asked how they felt about the initiative that had descended upon their store. “We love it!” they replied, predictably. But we felt like we needed to engage him more deeply.

So, we had decided to create an experience through which we would show him the (a) improvement process and tools that the team had used to come up with the visible changes and (b) thinking and skills that the team was developing. Concretely, we had decided to take him through a process study, followed by some rapid experimentation based on a handful of simple lean principles (e.g., produce one by one).

But he kept his hands in his pockets. And he gave me a look that seemed to say, ‘Executives like me do not fill out worksheets.’

In preparation, I had printed a few process study sheets and put them on a clipboard. After explaining what we had planned, I tried to pass him the clipboard. But he kept his hands in his pockets. And he gave me a look that seemed to say, “Executives like me do not fill out worksheets.” As you can imagine, we stumbled our way through the rest of the visit.

On that day, we failed to help the executive see the quality of the team’s improvement thinking and the practical validity of the improvement process they were following. Consequently, the executive left the store without learning deeply about the value-creating work and how the team could effectively tackle its problems. He also did not discover how he and others, such as the owners of the merchandising standards, could support the teams in carrying out this responsibility.

Fortunately, through subsequent visits, he did come to appreciate this approach. He even started experimenting with his leadership approach and the systems he and others were responsible for.

So, why do I share this story? For a couple of reasons:

You want better employees? Be a better employer.”

James (Jim) Womack, LEI Founder and Senior Advisor

First, as a leader, I encourage you to engage with the value-creating work that others are doing in your organization. If you do, seriously, you will develop a deeper appreciation for those folks in terms of their knowledge and skills to do the work and improve it. As my friends at the Good Jobs Institute like to say, “There is no such thing as an unskilled worker.”

Second, and very much related, you’ll come to understand how important your role is as an enabling leader, both in terms of your behavior (go see, show respect, ask why) and the systems that you help to develop and maintain. You and those systems either enable “everybody, everyday” to make things better or do not. As Jim Womack once said, “You want better employees? Be a better employer.”

Understanding Lean Transformation

Discover Why Your Lean Effort is Failing, and What to Do Differently.