Many leaders struggle to lead lean transformations. They are passionate and deeply committed, yet discouraged by the lack of engagement from others in the organization. Blaming senior leaders—or anyone else for that matter—for failing to be on board with the change, however, is not the problem. Those who are most excited about engaging in a lean transformation must look to themselves: they are often the ones who inhibit the process. They do so by failing to model the change they want to see.

Today Lean has evolved to the point where most leaders know that it is more than simply a system of applying tools. They understand the importance of paying attention to the way the work is done to achieve results and engage their people in PDCA learning cycles. They understand the leader’s role in embedding problem solving capability in people. And yet they struggle to create a lean culture that takes root. I believe this is because they are only “applying Lean” to the organization rather than “becoming lean” as an organization.

This type of work is challenging on many levels, and it can take a long time. In fact, many people assume that becoming lean is a decade long process. While that may sometimes be the case, becoming lean should also be ongoing and fun. And, there should be a significant and noticeable positive change in the culture that occurs fairly quickly. At some point between the first and second year, depending on the number of people involved, there should be a tipping point where the organization “comes alive.” This can be seen in improved performance fueled by high energy and an organization fully engaged in working holistically and creatively toward a better future state.

Are You Modeling The Change You Seek?

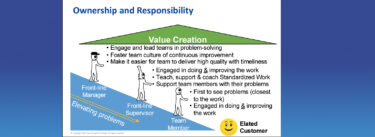

Creating this cultural transformation requires a new nature of leadership. The role of the leader is to lead this transformation, not by dictating tools or principles of Lean, but by modeling new behaviors that change relationships across the organization.

The key to this new leadership approach is modeling the skills to create mutually respectful relationships at all levels of the organization. These don’t always come naturally to all leaders, but we can learn from the few who have developed this capability.

In the early 1990s I was privileged to meet a successful transformational leader named Clyde, who led a quick (one year), but powerful change in a plant in Cleveland, Ohio. When he walked into this plant–which was the lowest performing facility in a large multinational company–Clyde noticed broken windows, a dirty and unappealing environment, and disgruntled employees. Within nine months, the employees disbanded their union, took personal responsibility for their performance, and created an exciting workplace. In just a few years, the plant was operating at the top of the company.

Clyde’s unique leadership was the key to this turnaround. He created respectful and trusting relationships with the employees. He listened to their problems and took personal responsibility for helping them solve those problems. He demonstrated empathy. These actions made a difference.

How then, can others learn from this? I believe that a core lesson from Clyde has to do with habits. Habits are deeply embedded and hard to change, but crucial to transformation.

Lead By Habit

Leader behaviors are habits; they are automatic. Our brain structure explains this phenomenon. Neuroscientists have learned over the last decade how behaviors and habits are stored in the limbic area (the old mammalian substructure) and emerge without any influence from conscious thought from the cortex (the thinking substructure). Consequently, it is not possible to simply think your way to behave differently. You need to practice it.

Your practice as a leader will in turn influence those you are trying to lead. Employees mimic their leaders’ behaviors. Over time, these behaviors grow and become engrained in the culture of the company. Most leaders try to affect change as if they are not a part of the system. They try to make others change, but fail to reflect on how their leader behavior is influencing the culture. Leaders need to practice modeling the behaviors of those like Clyde, which enable the organization to come alive.

Of course such a change takes more than superficial change. It takes more than grabbing lean tools and thinking they alone will create change. Forming, and especially changing, habits require us to be mindful and focused in analyzing our behavior. We have to reflect on our behavior and decide to enact change. We have to practice regularly and continue to reflect on our performance. Reflection and practice are essential for change.

Become the Inspiration and the Facilitator

Here are some essential methods to practice being the model for this transformation:

- Become a learner. In the book The Learner’s Path – Practices for Recovering Knowers, author Brian Hinken describes the difference between knowers, who spend time focusing on what they know and can tell others, and learners, who are observers that seek to learn from a situation. One way to build your learner skills is to pay attention to the social system in the present moment so that you can begin to understand the complexity of the problem situation. Ask questions like: Is the conversation a discussion, debate, or dialogue? Is there trust and safety in the culture? Keeping a focus on the interactions among people, instead of individuals, is an underlying principle to living the lean transformation.

- Create a respectful relationship with your employees. Listen to the problem situation from their perspective to demonstrate that you care. Start with humble, open-ended questions aimed at trying to understand their thinking about the situation and their approach to solving their problems. Resist the temptation to impose your knowledge and your thinking. Believe that they are bright and valued contributors. Support them when they need your help.

- Create a problem solving culture. Help everyone to see that problem solving thinking is more effective than solutions thinking. Demonstrate this by asking questions that expose the reality of the situation. Most organizations throw solutions at problems with no clear understanding of what is causing the problem. Start with a problem that is tied to the output of the business, define gaps in the performance of the value-stream, identify potential contributors to the gap, and engage the people who own that area in effective problem solving. Demonstrate that the employees’ efforts connect to the larger business system.

- Structure the learning through regular PDCA cycles. A leader not only deeply reflects on his or her own performance, but also guides this reflection process with the members of his or her team. The discipline of conducting regular PDCA cycles of learning is something leaders must model. Learning how to facilitate these reflection sessions will create a safe environment for exposing the real problems and addressing them.

It is important to acknowledge that you, as the leader, are attempting to build skills along with your people. In addition to your team, you have to live this change, or you will not realize the full potential of your organization to make this transformation. Modeling respectful relationships with your team will change your work, your organization, and your life.